The McKinney-Wilson Home: 35 Lincoln Parkway

Thomas J. McKinney c. 1931

Thomas J. McKinney c. 1931

Image source: Courier-Express

Thomas J. McKinney was a native of Titusville, Pennsylvania. His grandfather was an original settler of that region after the Revolutionary War and made a signficant fortune through lumber sales. His sons branched out from this position, taking advantage of the discovery of oil. Thomas McKinney's father made and lost fortunes in this exciting period, and ended up with a fortune when he sold his leases to Standard Oil. His father and uncle, began investing in tool manufacturing companies, including the Titusville Iron Works and American Radiator, the latter of which had three plants in Buffalo.

Thomas J. McKinney was described as "having retired from active business" a few years before his death. He was a harness racing enthusiast and owned stables at Seminole Park in Florida, where he had a winter mansion. He was instrumental in bringing harness racing to Fort Erie in 1932.

In the mid-1920s, he and his wife hired Buffalo's Esenwein and Johnson architectural firm to design a summer home for them in Buffalo at 35 Lincoln Parkway. With McKinney's interest in the details of the materials and design elements, the house took several years to complete. When finished, the McKinneys and their adopted son, Curtis, spent little time in the home before tragedy struck.

In March, 1933, the family was motoring in Florida from their stables to their winter home when an oncoming car that was trying to pass another vehicle lost control and struck the McKinneys broadside. McKinney's wife, Mary, died almost instantly; her husband, 48, died two days later. Their 11-year old son, Curtis, survived.

The nearly-new "million dollar mansion," as it was called, would remain vacant for nearly fifteen years.

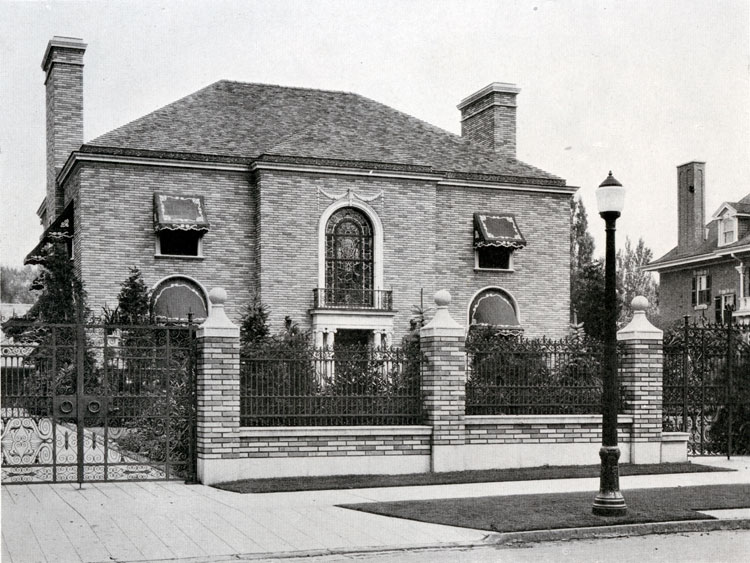

Front of house from Lincoln Parkway

The photos here were published in Beautiful Buffalo in 1931, just after the McKinneys moved into their new mansion from their temporary home at the Statler Hotel, where they stayed for nearly a year while 35 Lincoln Parkway was completed. The copper roof was estimated to have cost $90,000. The Jones Iron Works of Buffalo constructed the wrought iron gates, fence, window balconies and other ornamentation

.

Right side of house (from street) with gardens in view ahead.

The 9,000 square foot house was assessed in 1929 at $156,000, but the contractors who built it said it cost $800,000 to build and another $200,000 to furnish. Charles Berrick & Sons were responsible for the brick and stone work. Alvin W. Day Co. furnished the mantels, tile, marble and mosaics.

The garden with roses and fountains.

Looking toward the house from the gardens.

Looking toward the conservatory containing tropical birds and plants.

The sunporch.

View from the sunporch.

The drawing room.

This room was used as a chapel by the Catholic Diocese during the two decades it owned the mansion. Daily services and many marriages were performed here. The present owners, Clement and Karen Arrison, have placed a 1928 Steinway piano in the same location as the original, seen above in 1931.

The library.

E. M. Hager & Sons had the contract for the extensive hand-carved wood elements throughout the house.

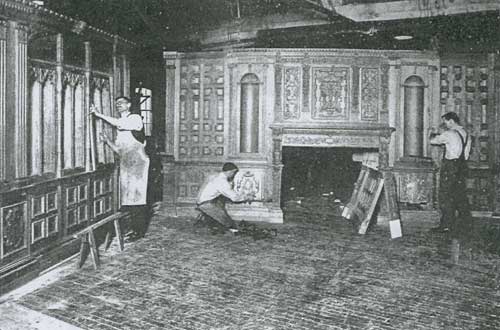

The assembly room at E.M. Hager & Sons where all woodworking elements of the library were assembled "to ensure a perfect fit" before delivery and installation.

The assembly room at E.M. Hager & Sons where all woodworking elements of the library were assembled "to ensure a perfect fit" before delivery and installation.

For eighteen months, twenty skilled woodcarvers, many hired from Europe, worked eight hours a day, six days a week, to complete the carving for the mansion. On the simplest pieces, such as a picture molding, one artisan could carve one foot in eight hours.

According to his obituary in 1954, George J. Hager "often considered as his outstanding masterpiece the interiors of the Thomas McKinney residence."

The breakfast room.

Entrance to the reception hall.

Panel carving, as well as some other work, was done from clay models. The carver molded a clay panel to serve as a pattern. When this hardened, it was placed on a easel and the carver began on his work with hammer and chisel, glancing from time to time at the clay model. (Note this in the upper left side of this photo from the Hager firm.)

Main staircase in the reception hall

Among the carvers were a father, Emil Lippicht, and two sons, Richard and Albert. They carved the lion, the great newel post and numerous garlands of fruit aruond doors and windows in various rooms. In 1949, they maintained a studio in Bowmansville, Lippicht Bros.

The story of the lion carving was related in 1949 by Hager vice-president and general manager, Walter L, Hoffmeyer: "We found a walnut tree in Alden that was thick enough through the trunk for the carving and we bought it from the farmer. Then we cut it down close to the ground and cut off a section for the lion. After the lion was rough-carved, we drilled a hole to the center of the block. Then we built a box and packed the block in wet sand, while an electric fan blew air into the hole we drilled. We put the whole thing in our kiln, where the temperature is kept at 180 degrees. Then for six months we sprinkled the sand every morning while the fan ran constantly, forcing the warm air of the room into the heart of the block. In that way, we dried the block from the inside out and prevented it from cracking when it was carved. But it was that hole drilled for drying that gave rise to a lot of talk about a secret compartment. The newel post itself is hollow, of course, because it's made in four sections to prevent cracking."

Another of the noted woodcarvers was John Hangan of Rochester who carved the English oak paneling and balustrate of the great staircase.

Balustrade in the reception hall (staircase at right).

In the

the mid-1930s, a wealthy Western New Yorker purchased the vacant home for $110,000. Kirke R. Wilson, known as "K.R," was born in Arcade with mechanical genius that served his ambitions despite a lack of formal training in engineering. He began repairing bicycles at age sixteen, was an early adopter of the automobile, first by designing a building a model with an air-cooled engine, then by becoming a dealer in Buick, and then Ford automobiles. In 1916, he moved to Buffalo and opened a repair company; over nine years there he designed nearly 1,000 tools for Ford repairs. After a number of years of attempting to contact Henry Ford, he finally succeeded. Ford was instantly impressed, contracted with K.R. to manufacture the tools, and thus began a lifelong friendship. Wilson established a factory in Arcade and would remain the sole owner of K.R. Wilson Tools for the rest of his life. It was written of him that his work absorbed him completely.

In the

the mid-1930s, a wealthy Western New Yorker purchased the vacant home for $110,000. Kirke R. Wilson, known as "K.R," was born in Arcade with mechanical genius that served his ambitions despite a lack of formal training in engineering. He began repairing bicycles at age sixteen, was an early adopter of the automobile, first by designing a building a model with an air-cooled engine, then by becoming a dealer in Buick, and then Ford automobiles. In 1916, he moved to Buffalo and opened a repair company; over nine years there he designed nearly 1,000 tools for Ford repairs. After a number of years of attempting to contact Henry Ford, he finally succeeded. Ford was instantly impressed, contracted with K.R. to manufacture the tools, and thus began a lifelong friendship. Wilson established a factory in Arcade and would remain the sole owner of K.R. Wilson Tools for the rest of his life. It was written of him that his work absorbed him completely.

Wilson's first wife died in 1927; their son died in 1929. In 1930, he remarried and purchased the home at 35 Lincoln Parkway in the mid 1930's for his wife. But they separated and neither ever occupied the home. Wilson had another home at 295 Depew which was his primary residence, but he also had a large home in Arcade that he had built for his father, a 100-acre summer retreat in the Bliss-Arcade area, and also owned eight farms in Arcade. He died in 1948 in the Hotel Statler-Detroit on a business trip. In a 1952 article, H. Katherine Smith described him as lonely. "He once said he refused to entertain acquaintances because he did not want people to pretend frienship for him merely to enjoy his generosity as a host."

After K.R. Wilson's death, the home at 35 Lincoln Parkway went on the market. The Catholic Diocese purchased it in 1950 for $35,000, despite the ongoing legal dispute about whether zoning laws permitted a religious structure in the neighborhood. Eventually, the Chancery of the Catholic Diocese moved into the mansion. They utilized the basement ballroom as a library. The home's library became the sacristy. The dining room retained its original function and, by happy coincidence, contained a carving of the coat-of-arms of Pope Pius II. Upstairs bedrooms became offices for the bishop and his staff. During their ownership, the Diocese also removed some windows depicting nude women and pagan images found to be distracting. Some elements were sandblasted to blur the details. The free-standing statuary was sold.

Lincoln Parkway entrance.

In 1985, the Diocese sold the home and in 2000, it was sold again for $980,000. Clement and Karen Arrison purchased it and began a painstaking and expensive restoration of the original design. They consulted with preservation architects and conservators and worked from a restoration plan. In 2011, the Arrisons were recognized for their labor of love by the Preservation Buffalo Niagara's award for Restoration.

For information about the archtitecture of the house and modern photos of the exterior and interior, see Buffalo as an Architectural Museum (takes you out of this site.)