The War of 1812 Visits Wales

|

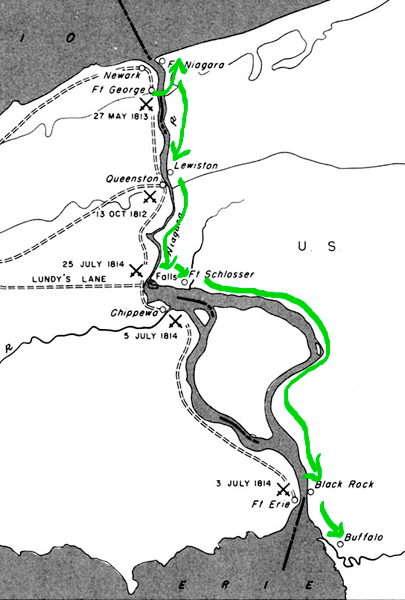

If there was one person to blame for the burning of Buffalo, Black Rock and every settlement along the Niagara River from Lewiston south, it would be American Brigadier General George McClure. He abandoned the captured British Fort George in Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) on December 10, 1813 and then, for reasons no one on either side of the conflict could then (or now) fathom, he ordered the village of Newark burned. The weather was frigid and snowy, the Canadian civilians were rendered homeless, and the act was condemned by all. When residents in the U.S. learned of this, they feared retaliation by the British. It was not long in coming. When Lewiston was burned the same day, the alarm went out as far as Avon and Caledonia on the east, all the way to Chautauqua in the south. Males over age 16 were "drafted," called up to serve in the state militia; all units gravitated to the Niagara frontier, especially Black Rock and Buffalo. Like Israel Reed of Wales (then called Willink), most called to the militia had only just settled in western New York on the few tracks that could be called roads. Reed had arrived in Willink with his wife, Margaret, and five children in 1811 and settled on Vermont Hill, so named because a number of Vermonters had relocated to that area. In the scant two years since his arrival, he had probably been able to construct a log home for his family and clear enough land to make some subsistence crops to feed his family and probably a cow and oxen. And now, in late December, he and every other weary pioneer looked at the conflict between the British and the United States with fear that they would lose everything, including their lives, if the British and their Native American allies continued their destructive assault. On the map at left, I have drawn the path of the British assaults in December, 1813, which culminated in the Burning of Black Rock and Buffalo. Image source: Buffalo Research. |

During the ten days after the capture of Fort Niagara, men untrained in any kind of military skills or discipline gathered into militia units named only by their origination: the Ontario militia commanded by Lt. Col. Blakeslee; the Genesee, by Maj. Adams; the Chautauqua, by Lt. Col. McMaham. Most were stationed in Buffalo, more than doubling its population of 1,415. But two units, under Lt. Col. Warren and Lt. Col Churchill, 382 militia commanded by Br. Gen Timothy Hopkins, were assigned to Black Rock, two miles from Buffalo. Israel Reed and his neighbor, Josiah Emery (whose descendents would donate his farm to Erie County for a park), were among those in Warren's group. Israel Reed was 45 at the time, asthmatic and disabled at the time with something resembling influenza. Why did he report to the militia? Because his eldest son, eighteen-year-old Benjamin, had been drafted but was ill, and his father took his place. What transpired in the Reed house as he prepared to leave is lost to history, but his wife gave Israel Reed a pair of mittens she had knitted for him. He would not be with his family for Christmas.

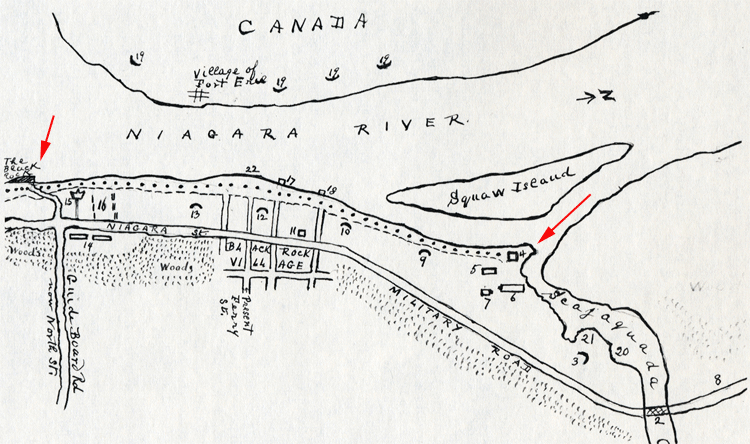

Hand-drawn map of Black Rock showing the landing places for the British assault of December 29-30, 1813. Image source: TBHM

Historian Merton Wilner wrote, "There was no surprise this time."

The Americans at Black Rock observed the gathering of British troops on Dec 26 and their intentions were confirmed the next day when a Canadian refugee crossed over and told American officers of the plan. Word was sent to Buffalo and Maj. Gen Amos Hall sent reinforcements. Not one regular army unit was available on the Niagara frontier to respond to an attack by professional British troops, known everywhere as the best trained troops in the world.

At midnight on December 29, 1813, the British began a two-pronged attack at Black Rock. The first group, two-thirds of the total force in this engagement, landed near what is now Amherst Street at Scajaquada Creek. They captured the Sailor's Battery. The American militia was ordered to advance and engage the British. Reed, assigned guard duty, traded places with another man, and joined the attack. When the British began firing, the militia was thrown into confusion in the darkness. Many fled into the woods. Reed and Josiah Emery were among the last to fall back. As they tried to hurry, Reed began to falter because of his medical conditions. Emery kept pace with him until Reed finally stopped and urged Emery to save himself. He gave Emery one of his mittens and asked that Emery give it to his wife. Emery left Reed his rifle and went on. He looked back to see Reed leaning against a tree, waving him off. Emery could hear the war whoops of the Indians close by.

In the morning, the second wave of British troops landed at the Black Rock beach. The Americans, reinforced now, resisted this assault, but then were flanked by the first group. All was lost and the militia fled down the Guide Board Road (North Street) and Niagara Street to Buffalo; others simply melted into the woods. The British and their Native American allies quickly reached Buffalo and put the little village to the torch.

"The Niagara Frontier now lies open and naked to our enemies. Your judgment will direct you what is most proper in this emergency. I am exhausted and must defer particulars till to-morrow. Many valuable lives are lost." Maj. Gen. Amos Hall to NYS Governor Tompkins, Dec 30, 1813, 7 o'clock p.m.

All of Western New York was fleeing east, those in Buffalo to Williamsville, those in Williamsville to Batavia. Some from Buffalo took refuge in homes that had been abandoned by their owners; many didn't return until spring.

The British re-crossed the Niagara into Canada on January 1, 1814. But the terror that had gripped the frontier, especially stories of the cruelty waged by the Native Americans accompanying the British, remained. In Holland, near Wales, on the Humphrey farm, local men constructed a triangular stockade covering nearly an acre, sinking 600-700 logs three feet into the ground with loopholes for firing. It is likely that more of these were constructed in the region as pioneers began to believe they were on their own against the British.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Black Rock, parties went around Black Rock and retrieved the frozen bodies of the 35 American militia killed December 29-30 and prepared to bury them. Israel Reed was found stripped of his clothing, stabbed twice with a bayonet, scalped, and with "terrible" tomahawk cuts on his arms. One of his rifles was broken in half and the blood surrounding his corpse suggested that enemy dead or wounded had been carried off. He had apparently put up quite a fight.

A man involved in the burials recognized Israel Reed's body and ordered a stake placed to mark the place so that the family could retrieve it and take him home. Word was sent to Wales and son Benjamin took a sled to Buffalo and brought his father's body home. Each way the trip would have taken at least two days over frozen roads. Close to Vermont Hill was the new Humphrey Cemetery (now along Rte 16). Reed's widow and children buried him there.

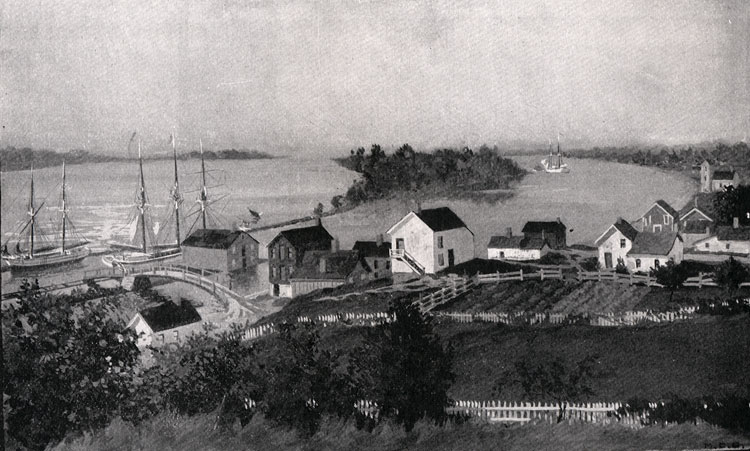

Black Rock in 1825, from a sketch of a sketch by George Catlin. Image source: Picture Book of Earlier Buffalo

Black Rock was rebuilt quickly, as was Buffalo. Fort Humphrey, as the stockade in Holland was called, stood for many years. Gradually, farmers pulled the poles for reuse in building barns. A marker on the Olean Road today is its only reminder.

The Reed family, like others whose husbands and fathers were lost in the War of 1812, faced years of hardship. The youngest, Charles, was 10 when his father was killed. He had no shoes and remembered for the rest of his life that he had to attend his father's funeral with his feet wrapped in rags. He recalled being sent to ask a neighbor for pork rind so his mother would have fat to cook the cakes for their meal. The family stayed on the homestead for a few years and then moved to Strykersville a few miles away. Benjamin, who was spared the Battle of Black Rock by his father, lived to be 83 years old. In 1819 he married Lucy Maria Stryker, daughter of the founders of Strykersville, N.Y. He and his family of at least 12 children moved around the country, living in Detroit, Indiana, Kansas and finally Missouri where he died. He was a farmer and a Baptist.

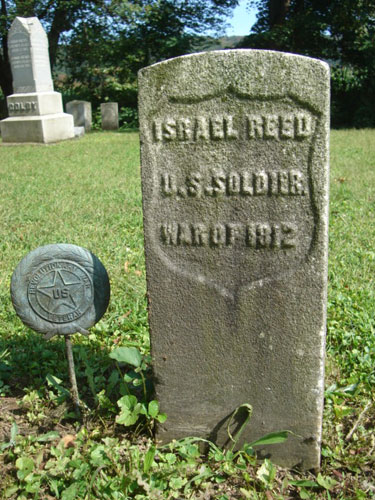

Israel Reed's grave marker, Humphrey Cemetery, 2008

Image credit: Donna Ruhland Bonning

Israel Reed's story has come down to us largely through an article in the Buffalo Illustrated Express in 1897. Son Charles' widow, Eveline Reed, recalled in detail many of the facts here. At that time, Israel Reed's gravestone in the Humphrey Cemetery was deteriorating. It was difficult to read the inscription: "In memory of Mr. Israel Reed who was slain by savages in the Battle fought at Buffalo Dec 30, 1813, aged 45 years." A former Town of Aurora Supervisor, Lyman Cornwall, doggedly pursued replacement of this with a proper monument to Israel Reed. He succeeded in having the U.S. Government place a standard soldier's headstone at Reed's grave and the other War of 1812 veterans buried in the Humphrey Cemetery. The original headstone was donated to the Buffalo Historical Society, which placed it on exhibit. In 2013, Israel Reed's replacement headstone is again fading.

Special thanks to Donna Ruhland Bonning, who properly photographed Israel Reed's grave stone in 2008 and posted it on the Find A Grave web. |

Reed's original gravestone, The Buffalo History Museum |