Brooks Locomotive

Horatio G Brooks c. 1885

Image source:

1899 Brooks Locomotive Catalog

Horatio G Brooks c. 1885

Image source:

1899 Brooks Locomotive Catalog

Horatio Brooks was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in 1828. Drawn to railroads from his early teen years, he began working in the shops of the Boston & Maine Railroad in Andover Massachusetts at age 18. There he eagerly learned locomotive construction and went on the become a fireman and then an engineer.

He went to work for the New York & Erie Railroad as an engineer and, when the line was extended in 1851 to a new terminus at the small village of Dunkirk, New York, Brooks brought the first locomotive into Chautauqua County via the Erie Canal and Lake Erie boat. He then spent six years as an engineer on the western section of the N.Y. and Erie, the longest railroad in the country at the time.

His interests lay with the railroad shops, however, and in 1860 he became Master Mechanic of the N.Y. and Erie Shops at Dunkirk, then rose to Superintendent of the Western Division of the railroad, and finally to Superintendent for Motive Power & Machinery for the entire N.Y. and Erie system. Then, in 1869, Jay Gould, having secured control of the company in a bitter struggle, retrenched the system and closed the shops in Dunkirk. Brooks successfully negotiated a lease for the property and went into the business of manufacturing locomotives.

By 1872, the Brooks Locomotive Works was producing 72 locomotives per year. By 1882, 200 locomotives were built a year for nearly every railroad in the U.S. In 1883, the company purchased the property and began significantly expanding its capacity. By the time Horatio Brooks died in 1887 at age 59, the Brooks Locomotive Works employed 1,000 workers.

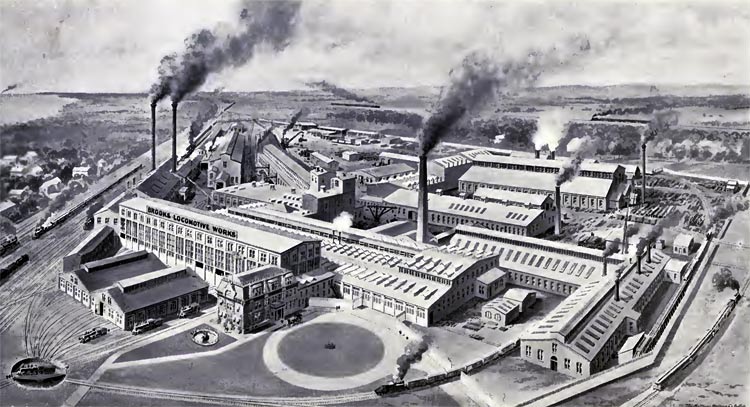

Aerial illustration of the Brooks Locomotive Works, 1899. Image source: Brooks Locomotive Catalog.

The Brooks complex covered 20 acres in the east side of Dunkirk, with 35 buildings. It produced its own electricity in a power plant, the first in Dunkirk, and used electrically-powered cranes in its shops. To produce steam and electrical power, the company used 400 tons of coal per week.

Horatio Brooks built an office building as part of the company's expansion, seen above left center. The first floor consisted of company offices, the second floor of engineers working on specifications and improvements, and the third floor was dedicated to classroom instruction. The Brooks Works offered the first vocational training in Dunkirk, open to Brooks employees 18 or older who could speak English, wanted to advance in the company, and were willing to attend classes three nights a week after their normal 10-hour shift.

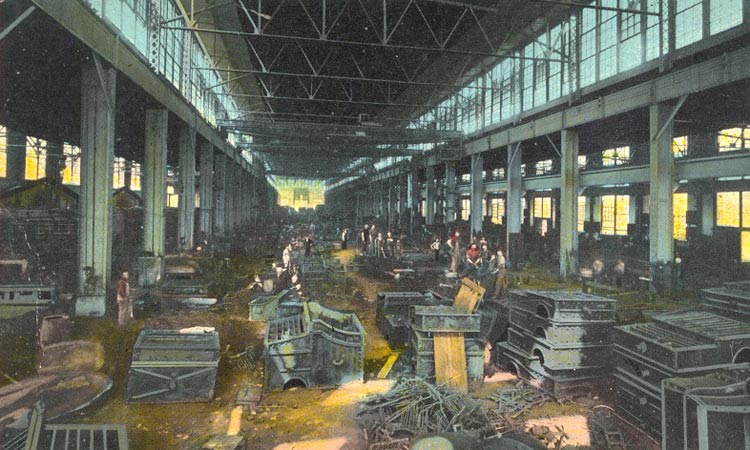

Erecting Shop, c. 1890s. Image source: John R. Stewart

The erecting shop had 16 pits. The electric cranes were 120-ton capacity, capable of lifting a locomotive as demonstrated in the above postcard. To control the smoke and steam emissions from engine testing, the 255-foot long shop featured brick ducts below ground into which portable exhaust pipes funneled the smoke, providing a safer working environment during months when the enormous glass doors seen at left needed to be closed.

Foundry, c. 1890s. Image source: John R. Stewart

The foundry building was 250 feet long and 100 feet high. Three large core ovens were served by electrical elevators carrying the iron and coke. The complex included two boiler shops with a total of 50,000 square feet of space, a machine shop, cylinder machine shop, carpenter shop, tank shop and a steam power house in addition to the electric power house.

Brooks locomotives were judged "Best in Show" at the 1883 Chicago Industrial Exposition. In 1898, the company produced its 3,000th locomotive. Now shipped to clients in other countries, Brooks assembled and tested each locomotive for export, then disassembled it for loading onto ships. A company "messenger" was sent abroad with each locomotive to supervise the reassembly and testing of the delivered product.

By 1900, Brooks Locomotive Works was the fifth largest manufacturing plant in New York State.

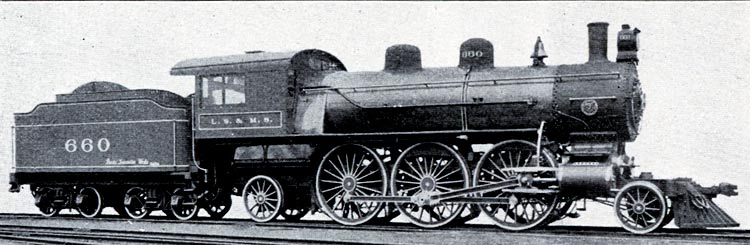

The "Monster" Locomotive, 660, on display at the Pan-American Exposition.

Images source: private collection

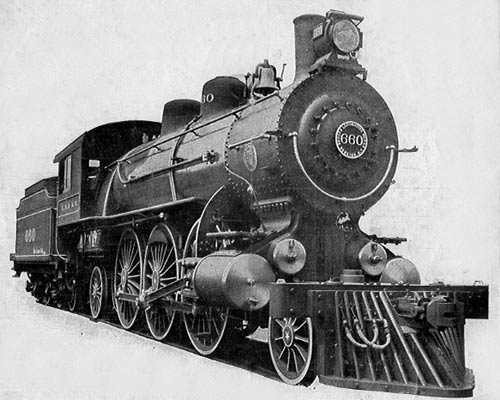

The 1901 Pan-American Expositon represented the last time the Brooks Locomotive Works would appear as an independent company. Its exhibit included a new locomotive, described thus: "The Lake Shore's exhibit at the Pan-American Exposition is '660,' a monster passenger locomotive, the largest in the world. While built expressly for the exhibit, after its close it will take its turn with its companion machines in hauling those famous trains, the "Lake Shore Limited" and "Fast Mails," in which others are at present engaged. Although the locomotives of this new type have been in service but a short time, they have already shown a sustained rate of speed of more than 75 miles per hour with a heavy train. The total weight of this engine with tender loaded with coal is 324,000 pounds. The cylinders are 20 1/2 by 28 inches and the diameter of the driving wheels 80 inches." It was 67 feet long.

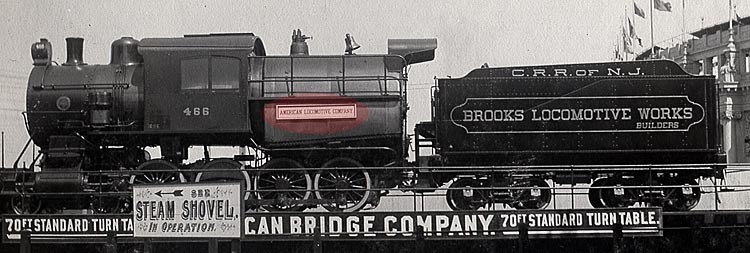

Locomotive and tender on a turntable at the Pan-American Expostion. Shaded area shows a plaque attached to the locomotive announcing the new company of which Brooks was a part, "American Locomotive Company." Image source: private collection.

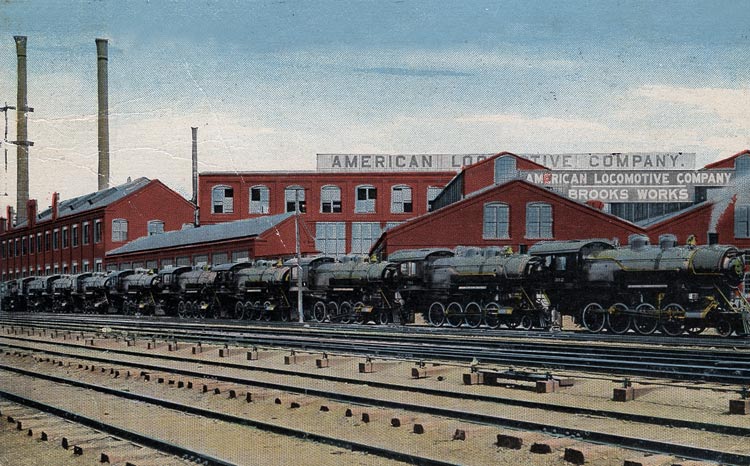

Postcard showing locomotives ready for shipment, early 1900s. Image source: private collection

Frederick H. Stevens, 1902.

Image source: Men of Buffalo

As the Brooks Locomotive Works, the company had produced 4,000 locomotives between 1869 and 1901. In its last year as an independent company (1901), Brooks had produced the most locomotives, 382, and paid $1,386,636.16 in wages.

In 1901, Brooks president, Buffalo resident Frederick H. Stevens, merged the company with six other locomotive manufacturers including the Schenectady Locomotive Works, to form the American Locomotive Company. The Brooks name would be retained as a secondary label. Within this framework, the Brooks Works prospered.

By 1921, the company employed 4,500 workers in the city of Dunkirk, nearly 24% of the city's population of 19,000.

In 1928, production of steam locomotives at the Dunkirk ALCO works ceased. After that, the company made spare parts. New work was found to utilize the capacity at Brooks when ALCO created the Thermal Products Division which made heat exchangers, pipe and high pressure vessels, custom made for refineries, power plants, water treatment plants.

The physcial appearance of the complex began to change when unused buildings were demolished. In 1938, the office building was removed.

Bing view of the former Brooks complex (shaded)

During World War II, the Brooks capacity for forging and machining large items was utilized when it produced two models of the 155-mm "Long Tom" artillery pieces. Its 800 employees also assisted with the Lend Lease program by providing locomotives parts for British and Russian allies.

After the war, the Brooks Works resumed producing custom products but times changed and the industries served shifted to standardized equipment made elsewhere. The complex closed in 1962, leaving 750 employees without work. A group of Dunkirk citizens bought the property and created Progress Park Industrial Complex. For a time, Roblin Steel, Plymouth Tube, Cendella Wood Products, Alumax Extrusions occupied the property. Cliffstar Corporation, maker of various beverages, utilized the former Brooks campus.

Horatio G. Brooks is remembered throughout Dunkirk, not the least for the hospital his children founded in his family's name, Brooks Memorial Hospital. Brooks found a home in young Dunkirk and, during the financial panic of 1873, did all he could to keep the employees on the payroll by operating at a loss until business picked up again. When Dunkirk was incorporated as a city in 1883, Brooks was elected mayor and served three terms. While he lived, it was said of him that, "He believes that life is too short to harbor resentments, and therefore has charity for all."