Influenza on the Homefront (Part 3)

October 1918 (cont'd)

Buffalonians had two significant factors that saved lives in the city. The first was was acting health commissioner Dr. Franklin Gram's actions to quarantine the city, closing all schools, bars, churches to public congregation. At the time he did so, the reported number of cases was more than 300. This closure had the effect of shortening the pandemic in the city. The second factor that assisted with reducing contact between residents was the coincidence of a city streetcar strike. All of the streetcar workers went out on strike on October 3 against the IRC (International Railway Company), in protest because the company refused to pay the wage award of the war labor board. The strike would last for four weeks, until October 27. The health department reported on October 14: "Never in the history of Buffalo has there been such a quiet Sunday. Between the street car strike on the one hand and every place where it would ordinarily be possible to go even by walking being closed, there was virtually nothing left for the people of Buffalo but to stay home and get acquainted with their families. This will help a long way in minimizing the possible spread of the disease.”

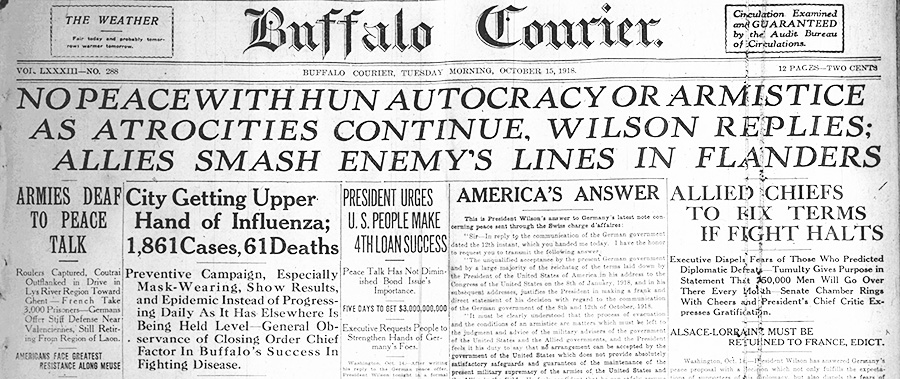

The October 15 front page of the Courier denotes the main topics on the minds of Buffalonians: the war, Liberty Loan campaigns, and influenza.

The worst of the pandemic was striking the city and surrounding counties. Mt. Morris, Groveland Station, Leiscester all reported a large number of cases on October 14. Things were particularly bad at Cuylerville where large numbers of immigrant workers employed in the Sterling salt mines had fallen ill.

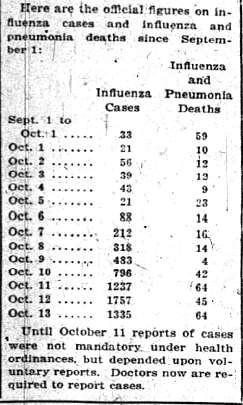

Although newspapers printed encouraging phrases about the decline of the disease, those same pages described the rapidly increasing number of deaths that occured.

Although newspapers printed encouraging phrases about the decline of the disease, those same pages described the rapidly increasing number of deaths that occured.

The only hopeful news from Washington, D.C. on October 15 was that new cases and deaths were decreasing in the army training camps. Since the beginning of the pandemic, 250,020 cases of influenza had been reported in the camps, with 10,741 deaths.

With some pride, the Courier reported on the same day that New York City wired Buffalo to ask for advice on how to deal with the influenza. Dr. Gram replied that "churches, schools, saloons and other places under the ban were closed and that the immediate effect was promising. The disease is not advanced in the geometrical progression noticed elsewhere and we already feel warranted in our action."

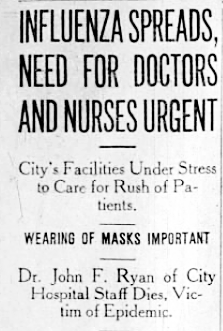

At the same time, Buffalo lacked sufficient hospital beds for influenza patients. Several hospitals were unable to accept more patients and others were crowded to capacity. The shortage of doctors and trained nurses forced the medical community to wire the War Department and ask that no more medical personnel be called up from Western New York.

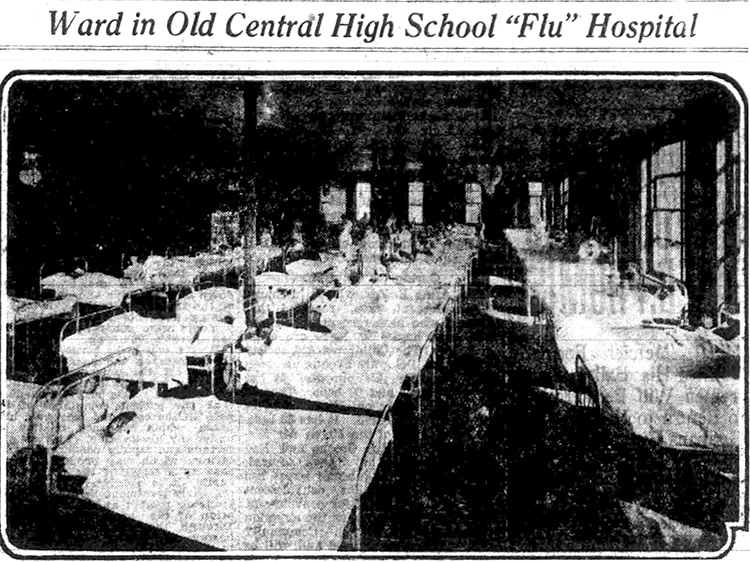

It was time to explore local facilities that could be transformed into temporary hospital wards. Dr. Gram met with other medical officers, Dr. Edward J. Meyer and Dr. Walter S. Goodale, to evaluate the options. The Elmwood Music Hall and Broadway Auditorium were rejected in favor of the old Central High School. That building, not used as a school since 1904, was being used by the National League for Women's Service as it headquarters and was fully functional with plumbing, heating, and appropriate rooms that could be converted to wards.

On October 22, there were 200 patients in the building and another 200 were on the way.

"Ward 3" at the Central High School October 22. More wards were being prepared when this photo was taken.

In an effort to obtain accurate numbers of those suffering from influenza, Buffalo teachers were asked to canvas door-to-door across the city. They did so, even as the papers announced on October 19 that 109 deaths had occurred in the previous 24 hours, bringing the total deaths in September and October to 703.

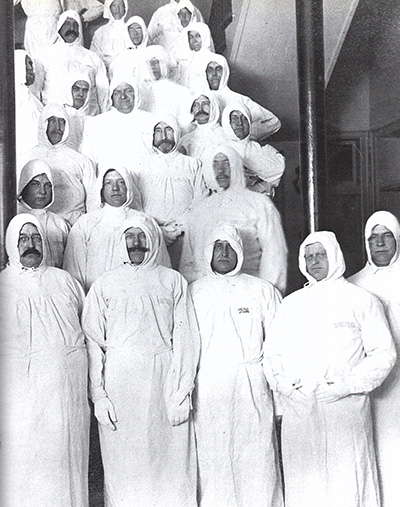

Buffalo physicians garbed to reduce contagion.

On October 16, 1918, the University of Buffalo senior class was pressed into service and the next day the junior and sophomore classes followed them into the hospitals.

When would it end?