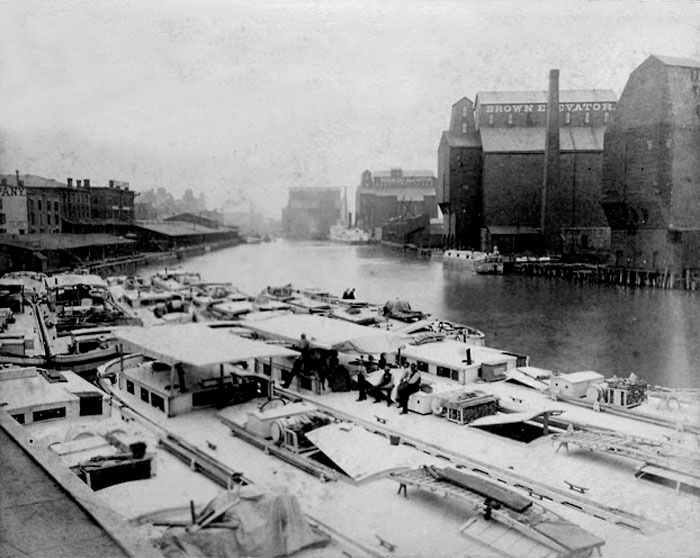

Canal boats parked along the inner harbor. Image source: private collection

Buffalo Express, February 19, 1905

Winter on the Canals

Enjoyable Features of a Life that does not seem very pleasant.

All So Snug and Cozy

And when you have your Home why not live in it, even it it is only a Canaler.

Snug and warm from the weather it seems in the cabin of the canalboat. And as for housekeeping -- the housekeeper on the boat is a genius. The boats lie side by side down in the canal in Buffalo, two abreast. The constant passage of the firetug through the winter makes it necessary for the waterway to be left open, so a rule forbids the jamming of the canal with boats as it used to be in former days.

The reporter knocked on the door of the stormshed, which is raised about the hatchway going down into the cabin and a fat black dog immediately appeared at the crack when the door was opened. The canal people are hospitable to visitors from town, although they sometimes live alongside one another a whole winter without every becoming neighborly. But another thing is noticeable -- a whole family may have to walk over the deck (which would be over the roof of a house) of another's boat all season, and they keep it up without so much as an unpleasant word and in fact with the most friendly relations throughout the time. Perhaps there is something about the life on the water that makes for peace of soul and forbearance in small things. Think of a family in town using another's veranda, say, all winter without any return.

All along the shore there rise the big buildings with their groaning engines and humming machinery, while teams go back and forth along the towpath. So long as the water is low or the storm shed is down on the boat, she lies as still as the water in the canal, but when the water rises or the wind sweeps against the shed, she groans and rocks and creaks against her moorings.

Down in the cabin went the gray-headed matron who is the owner of the boat. She is also the manager, her husband having died some years ago. The disappointed black dog followed. He wanted very much to take a trot into town to renew friendships there, but the fishermen along the shore have shown a marked fondness for the old dog, so his owners compel him to stay aboard. He has a history, this Rover of the canalboat. Six years ago, down in New York, he was strolling on the pier for days, evidently hiding from somebody. Then the canalboat came along and he stole aboard and refused to leave. so he got a job on the ship and has stayed ever since, with only an occasional attempt to take up tramp life again.

The cabin is the living-room, the sleeping-room, the dining-room and the kitchen, for the whole family. Amidships are the hatches leading to the hold where the grain and freight are stored. Away beyond in the bows are the quarters of the canalmen and the mules. "And," declared the head of the family, "there's not so thick a partition between 'em in Nature." The she went on in a confidentially injured tone, "People think the canal people are all of the same stamp. They think the owners are just another set like the drivers and other canalmen. They're mistaken. The canalmen work on the canal because they can't get anything else to do. They can always get a job on the water."

Her house was as clean as could be. It was a space just the width of the ship and about square. The steps were covered with oilcloth and so was the floor. In one corner was the kitchen with movable doors that slid back and forth, shutting the little corner in when need be. Right overhead was the opening for ventilation. Across the end was a bunk and at either side was another and each bunk had a set of drawers filling the space under it. Every little cranny and irregularity in the ship's sides was filled in by a cupboard or locker, and the household necessities and the clothing of mother and son and daughter were stored away in them. Everything is neat and in its place. One cranny, curtained off, held the family sewing machine. And under the stairs (the tops of the steps opened like boxes) were the rubber shoes and boots of the family. A red damask cloth covered the table and a plate of baked apples was set to cool on the dresser. It is a very homelike and old-fashioned nook, in the cabin of a canal boat.

"It's cheaper to live aboard, once you have your investment," the hostess explained. "Once we got frozen in up at Fort Plain and had to stay there all winter. The people were good and kind to us and there were plenty of stores around to keep in groceries, so it was just as good as anywhere else."

Canal boats near the foot of Main Street. Image source: private collection

In earlier times the canalboats tied up in the Erie Basin, but that is too exposed. After the experience of last winter's cold and storms they have mostly taken to the slips and canal. There are some twenty of them wintering on the canal at the foot of Erie Street and 27 or so in the Ohio Basin. Some of the boats stay at New York all winter, but the wharfage is so high there and the long stretch of docks so bleak that people don't like it as a rule. A loaded boat has nearly twice as much to pay for wharfage as an unloaded one. Some of them take a load in the fall to hold all winter simply for storage. There are so many expenses in connection with the business of the canalboat that it is only by keeping constantly busy that the owner is able to make it pay at all.

The woman took out a drawer in which were all kinds of things -- collars and cuffs, shaving apparatus, buttons and papers, and spreading out one of the papers on her knee, she pointed out all the items, explaining in the most businesslike way what each one meant.

"There are three classes of boats," said she. "It all depends on the age. Some of 'em go on for 30 years without showing old age, but the most of 'em are worn out after fifteen or sixteen years. A first-classer doesn't have to pay such high insurance to the owner of the grain. A third-class boat most always carries corn and such things - no wheat. And when she gets all played out they cut out her decks and make her into a coalboat. Yes, you get to know all the different kinds of boats and move around among 'em."

Right behind the boat lay others. There are five in one squadron. The leader is a steamer. She lies out of trim in the water now, for her machinery is in the stern (where the cabin of the horse boat is), and the bow goes up when she is unloaded. The other four are tows. A steam fleet is considered a sumptuous outfit on the canal. "But," said the cheery woman, "it is like everything else. There are advantages on both sides. There are advantages on both sides. There are the noise of the machinery and the trouble of keeping it in repair. One time that same fleet was down in New York tied up at the Hoboken wharf, when the big fire broke out. The smoke was so thick you could have cut it, and it was as black as ink. The captain thought he'd get out, an' he started up the engine. Well, she bungled around and got a log fust in her wheel , an' went limping in to the shore again, and he couldn't coax her away. So he cut the tows loose an' they drifted down to Governor's island, an' the steamer was burnt. That meant a big loss."

With the opening up of spring the canaler looks about for a load, and in a good season he does not have to look long. A commission-man happens to have a load ready, so the boat is filled with grain and stocked with provisions, and the trip down the canal begins. In the early spring, when the sun is just warm enough and the trees are all bursting into leaf along the water, when the moon shines softly down on an evening, "well, it's something like a picnic some days," the woman remarked, "but sometimes everything goes wrong. Then you wish you were in any other business under the sun." Down to Troy the boat takes its slow course. Every six hours the driver unhitches his horses or mules (the latter cost more, but are a better investment because of their superior endurance), the steersman comes along, and the bridge is put out for the tired animals to come aboard and the fresh ones to walk ashore and be hitched to the tow. The men change watches at the same time, too. Six hours off and six hours on, that is a canal mule's time, and a man's as well. At Troy men and horses are pretty well played out, so the horses are stabled and a tug is hired to take the boat perhaps right through to New York. It takes about four weeks to make the trip. Landing here and there and taking on extra provisions or changing the men, sometimes getting out of the boat and walking (for, "Captain, captain, stop the ship." is an easy matter to the canaler), and then taking ship again, the time passes. Sometimes the owner, if she feels like visiting a town, will take the train on and then wait for her slow craft to overtake her at the next landing.

At New York there is always something doing. The little boat may get lots of odd jobs during her stay. There are ships to be loaded from the cars and the canalboat hires a tug and plies back and forth with grain for all parts of Europe. Then the return trip begins. Time has gone on and the weather has waxed warmer, and the ship is no longer laden down so that she rides low in the water. So, in order to let her pass beneath the bridges the awnings must come down from the deck. The sun blazes down on the bare boards, and the cooking of the daily meals goes on in a very oven of a cabin. The men who walk on the towpath swelter and swear and the steersman, perhaps, tried to drown his misery, until the poor owner is nearly distracted, an declares it is no picnic after all.

A horse boat has six horses or mules, using three at a time, and four men, using two at a time. The steamer makes the trip much more quickly. of course, and has not the bother with the animals. It is almost as easy to tow two boats as one, and many of the canalers have what they call double-headers, that is, two boats running together. The steamer pushes one boat and tows the rest of the fleet.

"Yes," concluded the hospitable canaler, looking from the warmth of the stormshed across the snowdrifts on the decks that make the little floating community seem cosy and secluded, "there is a great deal of difference between a canalman and a boat-owner -- don't forget to say what nice people you met on board."

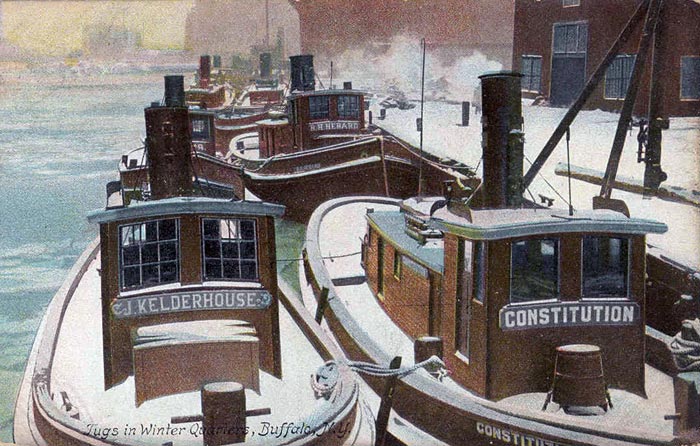

"Tugs in Winter Quarters" postcard. Image source: private collection.

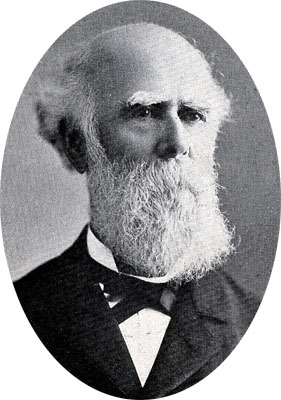

John Kelderhouse, 1900.

Image source: Men of Buffalo

The tugboat above, "J Kelderhouse," was named by its owner, John Kelderhouse. Born in Albany County in 1923, he came to Buffalo with his father on the Erie Canal in 1832. At age 22, he began in the business of wood dealing, supplying firewood to residents and to Lake Erie steamers. By 1861, Kelderhouse, noting that wood lots were becoming more distant and coal more prevalent as a fuel, decided to shift to building ships. His office was at 9 Dayton Street, in the heart of what is now "Canalside." (See 1894 map here.) At age 51, he married Jane Coatsworth, thirteen years younger than he. Over his long career, he had a major or partial interest in over 40 lake vessels, from schooners to wood and steel steamers, including a schooner he also named after himself. His tugboat was built in 1907 by Buffalo builder B.T. Cowles. Four years later, Kelderhouse died at age 87. His wife died six months after.

The tugboat lives on. In 1911, it was sold and renamed the Sachem. It sank four miles offshore on its way from Buffalo to Dunkirk On December 18, 1950. All twelve crewmembers died. The tug, however, was raised intact and sold to out of town interests which operated it for years. In 1990, it was sold to a Chicago company and renamed the Derek E.