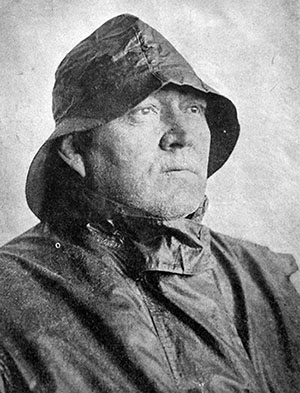

Captain Winslow W. Greisser: Commander of the Buffalo Lifesaving Station

"Kate Burr Meets Capt. Greisser - The Bravest Man in Buffalo"

The Buffalo Times, Sunday May 8, 1910

[ed. note: Kate Burr was a well-known feature columnist who spent 50 years on the staff of the Buffalo Times. This is her feature on Buffalo's Lifesaving Service and the man in charge. The text below is hers, brackets mine.]

...Those who are in a hurry go by the Lackawanna trestle, but climbing sheer precipices is not my strong suit, so I paused at the Bennett elevator where a man in the uniform of the Life Savers met me, and I was glad to leave the rickety landing-steps for the surer foothold of the Government ferry boat in the hands of a trained seaman.

...Here comes the Captain - men and women, let me introduce a real hero, though his quiet demeanor does not betray it and he will be the first ot sternly disclaim it.

Down in the office of Superintendent Edwin E. Chapman of the tenth district, United States Government Bureau, in the Federal Building, I saw the gold medal, Uncle Sam's highest award for "extreme courage in great peril," which was won by Captain Greisser in November, 1900.

When later in these columns, I tell you the story of that day's work, you will realize how one would rather have performed Captain Greisser's heart curdling deed of heroism that be President.

A strong-built man is the Captain, very quiet in manner and stern faced when in repose. But a smile of welcome or friendliness lights his countenance just as his lookout light flashing across the dark waters of Lake Erie smiles upon the entering craft of Buffalo's busy harbor.

A strong-built man is the Captain, very quiet in manner and stern faced when in repose. But a smile of welcome or friendliness lights his countenance just as his lookout light flashing across the dark waters of Lake Erie smiles upon the entering craft of Buffalo's busy harbor.

He is tanned as a sailor should be, by wind and exposure, but the blackness of his hair is lightened by the iron-gray of Time's color-box.

"I want something about you and the station," I said after a preliminary handshake.

"There isn't anything about me, and here's the station," said the Captain with a comprehensive wave of his hand about the place.

Captain Greisser, like many another man, abounds in titles.

His are deserved.

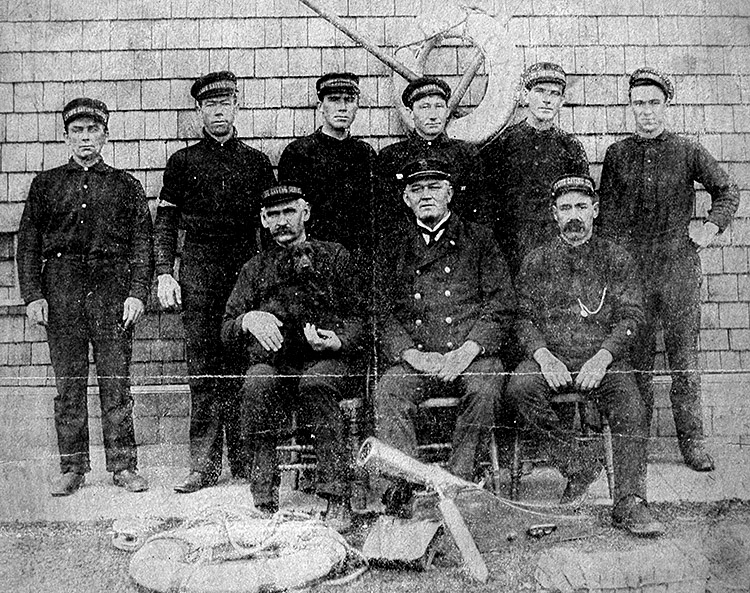

He is Captain of the crew of eight life-savers.

He is Keeper of the LIfe-Saving Station.

He is Master of three Government life boats which yesterday rested in shining whiteness of paint, and shining newness of trimmings on their stanchions in the boat house.

[undated photo of Captain Greisser at left is by Hare. Buffalo & Erie County Library]

Everything is spick and span about the station - that is one of the requirements - and there is a ready-for-action air about the men and the dog.

For "John" - the mascot of the crew, is always crazy to do when the danger gong sounds from the lookout tower.

Yesterday John's pointer nose was out of joint, for the crew - having no human beings to save, rescued a huge black dog who was trying to make shore from over beyond the breakwater and couldn't and John resented the attentions bestowed upon the stranger by motherly Mrs. Greisser and the crew.

Your neighbors don't bother you out in the station, but other things do.

Life there is one tense expectancy, from the opening of navigation, early in April, until the close of the season, about December 15th.

If anybody believes as I did, that a calm, summer day gives the life-savers no employment, let him be enlightened.

"Our small business begins just about now," said the Captain, "and lasts until the first of October.The heavy work is on for three months. It keeps us dancing."

"What's the small work?"

"Watching the excursion boats, the little river craft, yachts and so forth.

"We change lookout watch every four hours. One man patrols the beach at the same time. When the lookout leaves the tower he tells the story of the boats out in the river, the harbor and those that have gone into the lake.

"We change lookout watch every four hours. One man patrols the beach at the same time. When the lookout leaves the tower he tells the story of the boats out in the river, the harbor and those that have gone into the lake.

[1910 photo at right is the lookout tower. Buffalo & Erie County Library]

"The next man watches for these, and all that pass during his time at the watch."

"So you know where all the rowboats ought to be, and it they don't report, where to look for them?"

"Yes, that's our business - Sunday is the busiest day. It is a rare day when some mishap doesn't occur on Sunday. We expect it and keep a sharp lookout for trouble then."

"I suppose the fools who think they know how to manage a boat, but don't, give you plenty to do?"

"Yes," laughed the Captain, "they keep us from rusting.

"We keep in touch with the lighthouses, the horshoe light at the head of the river and the others. If they flash a light we always go to find out the trouble.

"One night two summers ago the lookout reported about 9 o'clock in trhe evening that the Horseshoe was flashing a signal.

"We manned a boat and rowed over. It turned out that the keeper had sat down by his kitchen table to read, and had left the door wide open.

"He never thought of our lookout taking it for a signal, but the watch only did his duty in telling me and I did but my duty in going, for there might really have been someone needing help."

Two or three little facts about the Life Saving Service may interest us here.

There are thirteen districts - three of them including the service of the Great Lakes. Nearly three hundred stations like the Buffalo house are placed at intervals along our ten thousand miles of coast line. In this district are eleven stations, with the one now building in Loraine [Ohio]. The service was originally known as the the Revenue Marine and was recruited from volunteers somewhat after the manner of the Volunteer Fire Department here in Buffalo. But in 1878 a full paid crew of eight men was put on.

Captain Greisser has been in the service since 1876, beginning at Marblehead, Ohio, where he remained until transferred to Niagara Station in 1893 and coming to Buffalo in April, 1900.

View of the entire U.S. Lifesaving Station, 1903. Image source: Buffalo & Erie County Library

I went all over the station - into the boathouse, where "The Valiant," the big twenty horsepower life boat for heavy work, thirty-four feet long, the handsome, taut little surf boat, ten horsepower and twenty-five feet long, and the twenty-six foot "B.B. Mcclellan," beach rowboat, only waited their chance for action.

In the boathouse are stored quantities of clothing, wearing apparel for men, women and children, for those who are unfortunate enough to lose theirs in a wreck.

These articles are furnished by the Women's National Relief Association of New York, which keeps all the Lifesaving Stations in the country supplied as needed.

The sailors' library is here also, but it seemed to me to have been read and re-read, and I wonder if the Buffalo Public Library can't help them out with one of its traveling libraries.

The crew, in sailors' vocabulary, call Captain Greisser "The Old Man."

"My wife could never understand," he said, "with some of them older than I am, always speak of me as 'The Old Man.' But that is universal at the stations.

"Ours," he said with a twinkle in the black eyes, "don't find me a very hard 'old man,' I guess, though of course we have to have discipline and an orderly way of doing things.

"As for Mrs. Greisser - the boys all go to her with their troubles and buttons. She sews on the buttons and smooths away the troubles."

Before I left I met Mrs. Greisser, and one glance at her face explained why the 'boys' all went to her with their troubles.

Some women are born mothers. They mother every human beign who comes their way.

That is Mrs. Greisser. One look at her face and you want to fly to her with all your woes. I even wanted to myself, although I never take mine to anybody.

"What is the daily routine when business is dull in the lifesaving line?"

"Well, we breakfast at six-thirty, do the room work - the men take care of their rooms, fill the lamps, get coal and so on - at seven-thirty. The remainder of the morning is spent in scrubbing and painting, cleaning and repairs - everything must be ship-shape.

"The afternoon is for rest and recreation, shaving, smoking, reading. The men sometimes turn in for a few hours - they must be rested, you know - ready for any emergency which may arise.

"Supper at half-past five - after that study flag signals - those drills are necessary. Then they play cards or spend the evening reading.

"They are entitled to a holiday once in nine days, but during the navigation season we have to be on the watch constantly here - this is a busy station - and they don't get a day off much oftener than once in thirteen days.

"Certainly, beginning with Sunday, we have muster, roll call and inspection. Every man must appear in uniform and his room must be ready for inspection.

"Then on Monday comes 'Beach Drill,' and overhauling the running gear.

"Tuesday and Wednesday are given to 'Boat' and 'Flag' drills - 'Going' drill on Thursday, 'Restoring the Apparently Drowned' on Friday and Saturday we clean house.

"Tuesday and Wednesday are given to 'Boat' and 'Flag' drills - 'Going' drill on Thursday, 'Restoring the Apparently Drowned' on Friday and Saturday we clean house.

"These of course are the rules and regulations for uneventful days but when the gong sounds from the lookout in warning everything goes by the board but the business of the hour."

"Of rescuing the perishing?"

"We are here to save lives and to prevent loss of life."

"What does the crew wear in action?"

"Oilers and cork jackets in rough weather, in summer white jumpers and blue trousers. In ordinary weather the regular uniform - this."

It is a plain uniform of dark blue cloth, double-breasted coat, the loose-flapping trousers of the tar, that Uncle Sam provides for his lifesavers.

The only ornamentation is a bit of gold braid around the Captain's cap and a few brass buttons on the coats.

"Tell me about some of your superstitions, Captain. Every band of men has some and I believe the sailor lad has his full share."

"Well," said the Captain with conviction, "look out for something to happen on the thirteenth of the month. I have observed that sign lately and it don't often fail."

"It is either a blow or a squall of some type.

"Then things happen on Friday. If it has been quiet all the week there'll be doings on Friday.

"Another sign - if one disaster comes - look out for three.

"And if the sea gulls are more than usually thick around the station, and flying low, look out for wind and storm."

"Do you have to keep track of people you rescue?"

"Yes, I have five reports to make every time the crew goes out. I enter the circumstances in the transcript and journal, also the wreck report book. In addition to these I send to Washington an account and one to Supt. Chapman.

"The report is detailed, contains the number of the crew, the time we left, the time we returned, the boat used, the people saved or lost.

"I must sent in names of those we rescue. One night a year or two ago a storm came up suddenly and the lookout signaled that two yachts.were in trouble out beyond the harbor.

"We went out, but after we picked a young fellow from one of the yachts and before we could reach the other it capsized and the young man aboard had started to swim to shore. He could never have made it that night, but we gathered him in.

"Well, he didn't want to give his name away because he had belonged to the Volunteer Life Service crew they used to have at Fort Porter and felt ashamed of having to be rescued, and besides that, his mother would try to prevent him sailing a yacht if she should happen to learn he had been in danger.

"So I took the name he gave, and gave him some of our clothing - he had lost two suitcases when the yacht capsized - telling him to return it.

"The next day, happening to look at one of the papers, what did I see but the young man's name and photograph, with a thrilling account of his narrow escape.

"The reporter had got it from the Yacht Club where he had taken his yacht from."

"Do you find any troubld making up your crews in the spring?"

"Well, yes. You see there are not so many sailors as formerly. The steamers, having supplanted the sailing vessels, there is not the demand for crews. It doesn't require sailors to man the travel boats.

"A man, to enter the lifesaving service, must have had three years' experience as a boatman."

1906 photo of Captain Greisser (center) and his crew that year. Image source: Buffalo & Erie County Library

"Do you like living out here - you certainly are not troubled by your neighbors?"

"I am glad to get back when I go away. Why, a few hours in town, dodging automobiles and hustling to get out of the way of the streetcars makes me call this Heaven."

It was peaceful at that moment - the blue sky looked down on the lamb-like lake, and I found it difficult to imagine that lake lashed into the fury that plays with a six-hundred foot freighter as if it were a paper boat, tossing it her and there in a restless rage.

"What do Mrs. Greisser and your daughter do when you are out in a big storm?"

"Oh, she is lookout watch then - they put in the time praying for us."

"We never go to sleep until the boat comes home," put in the Captain's wife. "There's always a hot supper waiting for them - and they need it, too."

"How about that gold medal, Captain?"

"Oh, that will tell you about it better than I can," said the Captain, pointing to a framed letter on the opposite wall, and blushing like a girl.

Superintendent Chapman told me before I went out that I would have a hard time finding out anything about himsefl from Captain Winslow Greisser. "He is the most modest and retiring of meen," said the superintendent.

The letter to which the Captain pointed so slightingly was the one which described his marvelous deed of heroism and announced the government award of the gold medal.

(There are two hero medals in the service - that for lesser heroism being of silver. But the medal of yellowist gold, awarded for extreme courage in great peril is the highest token of Uncle Sam's appreciation.)

While the Captain is attending to a matter of business and Mrs. Greisser is getting noon dinner for "the boys," let me tell you the story as the letter told it to me.

On November 21st, 1900, a great gale broke out over the lake.

They were building the breakwater at the time, and the man on the lookout watch reported that two of the stoneboats had broken their moorings.

The Captain and crew launched the big lifeboat and started for the scene, with the wind blowing eighty miles an hour and the greedy lake tearing and fuming her waves, like a wild beast licking her chops before devouring the prey.

When they had got about three-quarters of a mile to the windward of the scows and were bearing in, two great combers broke on board and a third caught the bow and pitch-poled (turning end over end) the heavy boat throwing the crew into the water.

The boat drifted down and came ashore at the station, and the crew, having found the workmen of the stoneboats safe on other boats, swam down to the station.

As Captain Greisser, exhausted from his tempest-fight, landed, word was brought to him that one of the workmen had come adrift at the "sand catch" and was clinging to a pile a quarter of a mile out in the surf. He instantly prepared for the rescue, against the protest of the crew and others, who said it would be certain death to venture into that boiling flood.

Captain Greisser only replied, "Wait, we will try! He cannot come to us, we will try to go to him."

Then Captain Greisser and Greenland of the crew dashed into the lake with a bowline fastened around the captain.

A hundred yards from shore a huge wave struck them down and knocked Greenland unconscious.

The Captain started again alone, the surf dashing over him, and hiding him from his men who held the line on shore.

Several times he was beaten back a hundred or two hundred feet and a floating telegraph pole struck him in the back, knocking him almost unconscious.

But at last the intrepid Captain reached the imperiled man who clung to the pile begging piteously to be saved.

The line was fastened about the workman's waist and the Captain was ordering him to jump into the waves when he discovered that the bight [loop] of the line had fouled in the center and wound around the piles.

After fifteen minutes of the most hazardous work he unwound the line and, and told the man who had cried that he could not hold on longer to jump.

The crew pulled the man ashore unconscious, while the daring Captain plunged again into the surf and swam home, falling at the feet of his men in a stupor.

Both men were carried to the station and resuscitated.

It reads grandly, doesn't it? Like some far-off deed of valor,yet this chivalry belongs right here in Buffalo, and the glory goes to one of their citizens who will shrink to read this scant praise here today.

"Did the man ever thank you, Captain?"

"I never saw him afterward - but I only did what I am here to do."

They made the Captain a member of the "American Cross of Honor" for that deed. It is the Victoria Corss in England and the Iron Cross in Germany.

They made the Captain a member of the "American Cross of Honor" for that deed. It is the Victoria Corss in England and the Iron Cross in Germany.

No one but those who have won the lifesaving medal of honor from the government can belong to this organization, except the President of the United States, by virtue of his high office and the rulers of certain countries who by reason of thier exalted stations are heads of similar societies of the distinguished order. Also philanthropic persons who shall found and endow societies to encourage the saving of life.

The insignia of this noble order is a Maltese cross of gold and crimson enamel. It has been conferred upon the Emperor of Germany and three Presidents of the United States.

A measure now before the Senate Commerce Committee, providing a retirement and pension feature in the governing laws of the lifesaving service, and for longevity increase of pay for employees, has just been endorsed by Secretary MacVeagh of the Treasury Department.

I believe you can't overpay men for saving life,and I hope the measure will go through.

When I went over there I yearned for thrilling adventure - either to be in at the death at a rescue, or to be rescued myself somewhere out in the wild waves of Lake Erie.

None of these desirable experiences wer mine, but I had one I would not part with after all.

I had met face to face the quiet man who is recorded in the government's log book as the bravest man in Buffalo.

[Image at left of the medal. Image source: Internet]

[Note: Captain Winslow Greisser, an Ohio native, returned to Ohio the next year when the new Lorain Lifesaving Station was opened. He finished his career there and died in 1931 at the age of 85.]

For information about the Buffalo Lifesaving Service Station, see my page here.