Dunkirk's Point Gratiot Lighthouse

"The light must be kept burning. " Francis D. Arnold

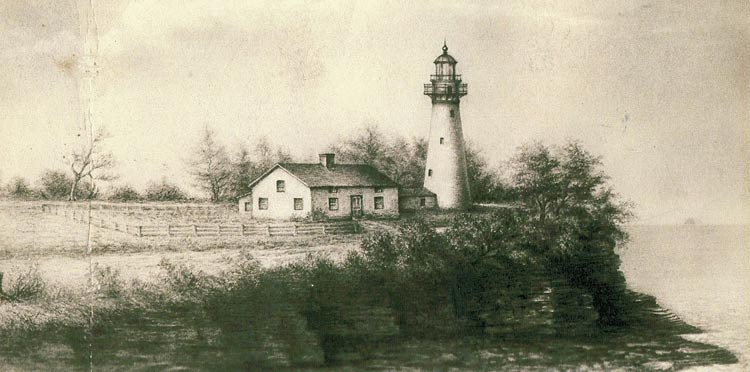

Drawing by artist George A.H.Eggers in 1865 of the first lighthouse (1826) on Point Gratiot in Dunkirk.

Image source: Dunkirk Lighthouse & Veterans Park Museum

The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 transformed the Great Lakes into the most economical transportation system between the Middle West and the Atlantic Coast. Grain, lumber, and coal began to flow east, and manufactured goods and settlers flowed west. The need for safe navigation on the Great Lakes was immediately recognized by the federal government's Lighthouse Service. Dunkirk, with its natural harbor, was an important port on Lake Erie and a local citizen, Walter Smith, secured the establishment of a lighthouse on land he donated at Point Gratiot. This lighthouse, constructed in 1826-27 with local stone, bricks and ironwork, was one of the early Lake Erie Lighthouses. It used whale oil to light the lamp and reflector sytem that cast the guiding light. When the federal government funded a breakwall for the harbor in 1827, a second pier head light was installed. The lighthouse keeper was responsible for maintaing both.

The 1875 lighthouse with outbuildings for the keeper's animals, date unknown.

Image source: Dunkirk Lighthouse & Veterans Park Museum

Lake Erie's waves eroded the bluff on which the 1827 lighthouse was built and, in 1876, a new lighthouse was constructed nearby. The old lighthouse's 61' round siltstone tower was dismantled and rebuilt for the new lighthouse and its 1857, third-order Fresnel lens, re-installed. The new brick lighthouse keeper's house was in the Gothic Revival stick style and, to keep the style consistent, the round stone tower was "squared" by a limestone exterior.

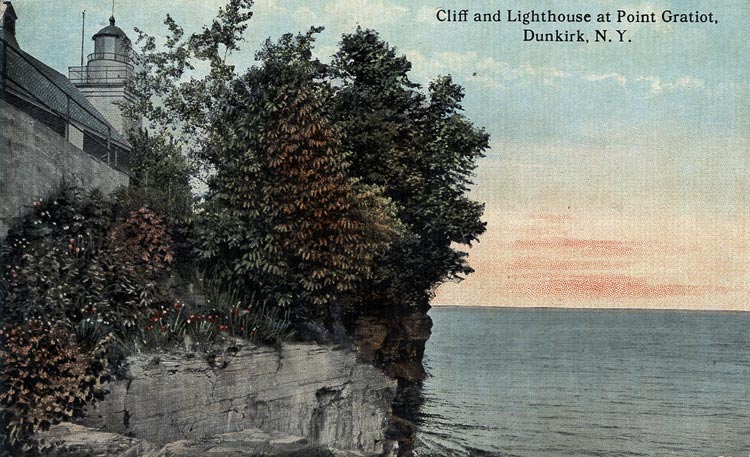

Lighthouse viewed from the lake. Image source: author's collection

The lighthouse keeper lived with his family in the brick home provided by the federal government, which also provided fuel and materials for the maintenance of the light and lighthouse property. A very small salary was provided and the keeper was expected to operate his own small farm and feed himself from vegetable gardens, chickens, cows, goats. Charles Arnold, son of the longest-serving Dunkirk keeper, said in the 1990s, "There wasn't any fancy stuff."

The Fresnel lens, nearly 6 feet tall and 4 feet wide, was lit by whale oil fuel for a short time, then rapeseed oil; after the Civil War, lard oil became standard. Kerosene was introduced in 1877 and was the dominent illuminent until the conversion to electricity which, for the Dunkirk lighthouse, was in 1923. The light could be seen for 17 miles in the 19th century. Dunkirk's light was among the most prominent on the southern shore of Lake Erie, situated atop a 20-foot bluff.

View from the cliffs of Point Gratiot, showing the setback of the lighthouse. Image source: author's collection

The light operated with a clock mechanism of weights and pulleys which required winding every four hours during the night to keep the light rotating. The lamp consisted of three panels that revolved so the light shone for six seconds with a four-second gap between flashes. Each evening at dusk the keeper or assistant keeper traveled to the pier light in the harbor to light that beam and then returned to the Point Gratiot lighthouse. His job was to open the curtains inside the lantern and remove the linen cover over the lens, both of which were needed during the day to protect the lens from the sun. During the night, the keeper and assistant often split the night shift, with one person awake to make sure the light continued to burn.

2012 view from the lighthouse. Shaded area is the location of the first lighthouse. The submerged outline of the eroded bluffs in the old postcards above is visible.

During the day, the keeper and his assistant refilled the fuel reservoirs in the lighthouse tower using a dumbwaiter. They kept the windows of the lantern clean and resistant to window-fogging steam using glycerine. The lens was dusted every day and several times a year completely washed and its brass fittings polished, a task which took keeper Francis Arnold a week. When light maintenance was completed, the keeper was responsible for whitewashing the lighthouse tower and the harbor's pier light each summer and maintaining the grounds. The Lighthouse Service sent inspectors annually to each lighthouse in the country.

The lighthouse did not function in winter when there was no lake navigation. The light was turned off for the season in late December when the last tug passed and was lit again in spring when the first boat was leaving Buffalo. During the winter months the keeper painted the interior of the buildings and performed structural repair as part of maintaining property owned by the government.

Current view of the lighthouse and keeper's house from the lake side.

Francis D. Arnold, 1935.

Image source: Dunkirk Lighthouse & Veterans Park Museum

Francis D. Arnold, called "Dea," was the longest-serving Dunkirk lighthouse keeper, beginning in 1908 as assistant keeper and becoming keeper in 1928. He retired in 1950, having raised with his wife six children whose memory of their years there were happy ones.

Mr. Arnold saw the implementation of electrical lighthouse beams in 1923 which would eliminate the need for an assistant keeper. The same Fresnel lens installed in the original lighthouse in 1857 continued to magnify the electrical light so that it could be seen up to 24 miles on a clear night.

As keeper, he continued to be responsible for making sure the light beamed all night, seven nights a week during the shipping season. He was also the first responder for any ships that ran aground, expected to assist the unfortunate onto land and take them into his house, feed and warm them. And, after the Coast Guard absorbed the U.S. Lighthouse Service in 1939, he reported such incidents to his supervisors in the Coast Guard.

There were no special qualifications for becoming a lighthouse keeper. One applied to the Department of Commerce and, if hired, learned the trade from the head keeper. Mr. Arnold was very proud of his job, according to his children, who said that "He would have been a good Sergeant in the Army. Everything had to be just so." Each morning, he dusted the Fresnel lens with a feather duster or polished it with a chamois. He surely passed the frequent, unannounced inspections by the Coast Guard with flying colors.

Despite the meager salary, which in 1928 when he began as lighthouse keeper was around $560, he told his children they were living on an estate. He enjoyed having people visit the lighthouse and climb the spiral iron steps to the top of the tower, particulary what he called "young love." A number of proposals occured atop the tower, possibly inspired by Mr. Arnold's radio which he placed at the bottom of the stairs, playing love songs loud enough to be heard by the couple at the top.

2012 view from the land side.

Mr. Arnold retired in 1950 and a few more lighthouse keepers served until the Coast Guard closed the lighthouse in 1961, terminating its function and replacing it with a higher-intensity pier light in the harbor. But repeated incidents of private and commercial craft running aground and the difficulty of seeing the harbor light when approaching from the west spurred the Coast Guard to reverse its decision and the light was turned on again, permanently, in the spring of 1962. Today, the lighthouse operates automatically, its illumination created by a 4-place lamp changer which rotates when one bulb fails. The Fresnel lens continues to magnify the beam. The light from the the lighthouse flashes 6 seconds on and 4 seconds off.

In 1979, the lighthouse was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and, in 1984, the Coast Guard turned over the lighthouse and grounds to a new museum which has become the Dunkirk Lighthouse & Veterans Park Museum. The Coast Guard is responsible for the lighthouse light; the museum volunteers keep an eye on the 4-place lamp changer and notify the Coast Guard when it needs replacing.

The non-profit organization conducts guided tours of the lighthouse and keeper's house. Part of the house and an adjacent building contain military exhibits. For more information, look here.

Grateful thanks to the lighthouse museum tour guide Pam Comerford and vice-president Dave Briska, for their assistance and permission to use images.

Special thanks also to Dunkirk Historical Museum president, Diane Andrasik, and volunteer Denise Griggs, who located newspaper articles relating to the lighthouse and the Arnold family.