Working in a Theater: the Illustrated Buffalo Express, February 5, 1910

Note: The theater referred to in this story was the Teck Theater at 766 Main Street. Images below were taken by Hare using "flashlights" and are part of a private collection.

Photo captions are original. The article, excerpted below, was written by L.E. Moss. To read the entire article, look here.

caption: The electrician meets a problem.

When the day’s work is over, and brilliantly lighted streets and festive throngs, motors, packed street cars and closed shops tell of a long evening of rest and pleasure for the city, one class of laborers sally forth to begin the day’s labor. Gay throngs file into the theaters and the orchestra strikes up its first strains, then the curtain goes up, and the mind is lifted clear out of the rut of everyday in contemplation of the idealized scene on the stage,as marvelous as modern ingenuity can make it. Then it is that back there, in the dim light, a corps of men toil for their living – men whose lives are spent in the theater, but who never see a play.

The glamour of the theater draws little Johnny around to the dingy, bare brick wall wherein is situated the great, mysterious stage door. He

watches the loads of stuff coming in from the station, watches busy men unloading it and depositing it within the cavernous gloomy door. Johnny is of working age and he wants a job. He hates school. So he slides up to the stage manager and asks to be allowed to go to work on the stage. He is taken on, and told to come around that evening at 7:30 o’clock. So Johnny fairly treads upon air as he sets forth – to be forever within the theater, to need no costly tickets of admission – to be one of the chosen few, so Johnny feels. It is a specially big production, and many extras are needed. The week ends, Johnny is taken on permanently as a clearer at 50 cents a performance. The theater has claimed him, and thenceforth his lot is cast behind the scenes, in that bare and draughty outer circle from which is shut off the little space of the stage room wherein night after night is concentrated the whole essence of the theater.

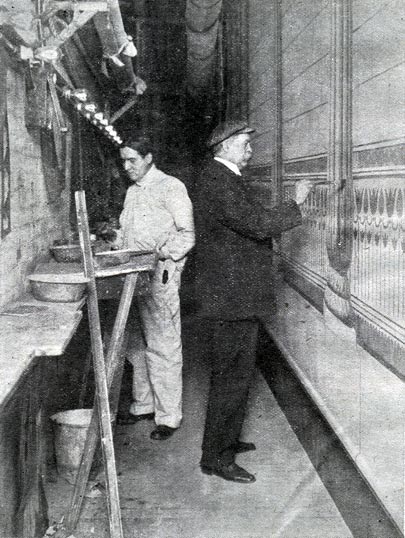

caption: The scene painter

align=:justify"Night after night for five or six years Johnny lounges in the wings with half a dozen other dingy figures, telling scraps of stage gossip in whispers, speculating as to the success or failure of the piece, whispering of omens noted (for these stage folk are unconquerably superstitious), stealing as close as possible to the edge of the scenery, peeping eagerly from behind a stage rock or hillock or tree trunk, or finding a thin place in the canvas, an eyehole, and appropriating it.

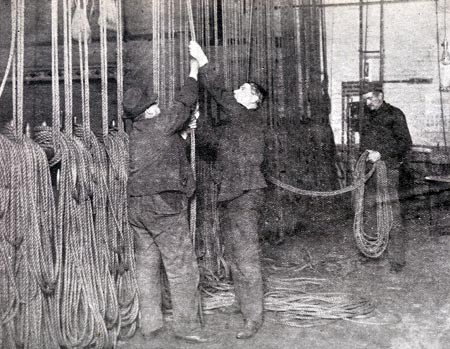

caption: In the fly gallery

There are many thin spots in the canvas after it has been rolled and unrolled and handled half a season, and the stagehand that finds a place of vantage glues his eye to it and drinks in the play – wrong side about. There is Maxine Elliott, standing with a hug apple bucket in either hand, her red hood slipping from her black hair – the buxom Devonshire maiden. Down there within the dark semicircle where hundreds of people sit watching, a roar of applause rings to the great arched ceiling. The actor stands in the orchard gate with the beautiful scene behind her of heavily laden trees, very realistic, yet very idealized. Johnny, with his eye to a hole sees her standing there surrounded by crazy, irregular framework, filled with dingy grey canvas.

Except for the light that filters through between canvases, the stage is as dark as possible, lest a stray reflection should mar the carefully studied lighting effect within the picture. And, except for the queer, long-distance stage voices in the play, the stage is utterly silent. Should anybody cough audibly or sneeze or speak, the stage manager is after him, on tiptoe, but bristling.

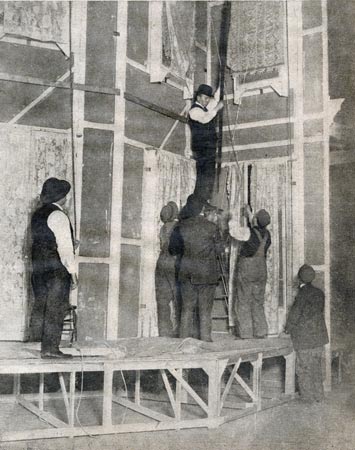

caption: Stage hands rehearsing a scene. View from the front

Just within the screen of the canvases, and waiting with ear and eye strained, stands the queer figure of the rosy farmer’s wife, with a tea making outfit in her hands. She jostles past Johnny, who immediately shrinks up out of the way, and as the actors come near a certain point in the dialogue she waits her cue – the word or action that is the sign for her to come in. In she goes, but there are other actors waiting yet. And now they are all on stage, and beginning to come off again and away they fly to the dressing-rooms, and the stagehands are left in possession of the eyeholes once more. And now down comes the curtain and the call to “strike.”

Everybody awakes from the trance of silence and hither and thither they rush. Everybody has his appointed task. There is the property-man of the company directing the clearers – the little chaps who hustle about dragging off the furniture, the stage carpenters and his boys pulling the great canvasses out of the way and the electrician and his assistants switching off certain lights, switching on others, regulating everything in accordance with the plots of act II. And, not to be forgot, away up above and out of sight, the busy flymen, in their pitchy black gallery, above the stage seize the ropes from the belaying pins and haul for dear life. Like the sail of a great ocean ship up, up goes the back drop, up one after another go the wood borders – those cutout affairs, that give the effect of overhanging branches, ivy or roses. They are just like sails, a foundation of almost invisible net for the flimsy painted foliage. Up they all go. Those flymen are  wonders in their way, and it takes a pretty competent stagehand to manage the flies. Imagine a gallery, high up in the loft above the stage, with a gridiron of rafters far above it again. And over these close-woven rafters are swung the lines. Short, center and long lines they are called, for they go in sets of three. The short one is attached to the top of the scene nearest the stay pins, the center to the middle top, and the long line to the far edge. And it takes some muscle, and a certain knack, too, for a man to haul in those three lines at one operation, and lift the sometimes heavy weight of painted canvas until it swings high above the stage in the darkness of the outer void. And to know just what pin governs each set – to pick it out from the 150 set, at a minute’s notice and without hesitation or the loss of a moment, to get it out of the way and just the right canvas for the next act lowered to the stage – well, you and I couldn’t do it. It takes a full-fledged member of the Stage Mechanics’ Union on anything from $18 a week and up. So from the flies are manipulated the drop scenes and hanging pieces, while down on the stage other chaps bring on the frame scenery and set it up.

wonders in their way, and it takes a pretty competent stagehand to manage the flies. Imagine a gallery, high up in the loft above the stage, with a gridiron of rafters far above it again. And over these close-woven rafters are swung the lines. Short, center and long lines they are called, for they go in sets of three. The short one is attached to the top of the scene nearest the stay pins, the center to the middle top, and the long line to the far edge. And it takes some muscle, and a certain knack, too, for a man to haul in those three lines at one operation, and lift the sometimes heavy weight of painted canvas until it swings high above the stage in the darkness of the outer void. And to know just what pin governs each set – to pick it out from the 150 set, at a minute’s notice and without hesitation or the loss of a moment, to get it out of the way and just the right canvas for the next act lowered to the stage – well, you and I couldn’t do it. It takes a full-fledged member of the Stage Mechanics’ Union on anything from $18 a week and up. So from the flies are manipulated the drop scenes and hanging pieces, while down on the stage other chaps bring on the frame scenery and set it up.

caption: The same scene as above, from behind the set.

A little interior effect is being rapidly shaped down there on the stage. The men shoulder and bring in huge pieces of framework, lifting and balancing it with the knack of long experience and setting it down to the exact line marked on the ground cloth for that scene. The back and sides have been placed, and the backings set in place, (the pieces that give the illusion of something beyond a door that has to be opened during the act) so that no matter where your seat may be in the whole house, you cannot see around them.

And with a quickness that is startling these men begin to “snap” the back and sides together – snapping a thin, strong lash, to catch the series of metal hooks alternately on one piece and then the other. Seldom do they miss their mark, and in a twinkling the house is laced together. From above comes down the little ceiling aimed so precisely that it falls exactly upon the top space and is snapped securely there. These pieces of canvas, made as they are to give the idea of perspective, present some odd shapes.

It was a in a play that depicts New York. There were windows in the little house set up, and these looked out on the wall of an apartment-house. Between the two shone the outer daylight and the electrician was now busy getting his strip lights into place to shed morning light within that space, and indoor light within the house. One thousand white electric lights there are above the stage in a big theater and various colors and gelatin sheets and what not, to tint the light to soft grey dawn, rosy sunset, glaring midday or twilight as the case may be. Perhaps there is no other craft so comprehensive as stagecraft. The designing artist who plans the whole effect for a play, of scenery, lighting and postures for the actors, must be sure of close sympathy in the man who paints the scenes, the man who understands electricity and carries out his ideas, and the stage carpenter who makes and places the scenes. And all must be in sympathy with the actor folk.

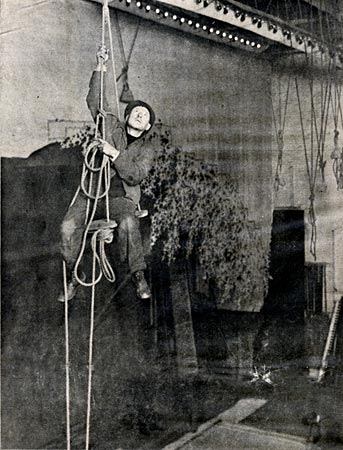

caption right: Climbing to release a fouled rope

It was in the biggest theater in Buffalo, that great structure built originally to accommodate masses of German singers on its stage. The old red brick walls, lost in shadows, and high above, the gridiron with its maze of ropes, some holding scenery, some hanging idle, tied in sets and hooked to sandbags to bring them down – it is a vast stage, capable of staging almost any production. Along the side wall you ascend by steep and narrow wooden stair to that dizzy height, and tread in the cobwebby twilight past an old painted mantlepiece, some queer bits of furniture and other odds and end that accumulate about a theater, and are raised and lowered when needed.

caption left: Some stage sets and properties for "Way Down East"

“Isn’t it dangerous for the men up here?” was asked, as men were seen leaning over the balustrade that alone shielded them from a fall to the stage so far below.

“No. They get used to it. We have had a couple of men fall, but never a serious accident. One fellow fell through several pieces of canvas and was caught by another stagehand at the bottom, not even shaken up.”

------------------------

Sometimes, you know, we have to jump out of a place at night right after a performance and catch a train for the next stop – and set up again ready for the next night. Sometimes we leave in the morning in the middle of the week, and there’s another company coming in at the same time. Our men are hard at it taking down scenery, getting the properties out of the way and sent off on the train, and at the same time there’s the other show bringing its stuff in and putting up scenery. Then, the hands have to use their wits to see that they don’t take out something that’s just been brought in, or bring in something that’s been taken to the wagons.”

caption: Eva Tanguay in "The Follies of 1910" Star Theater

Salaries

Current equivalent dollars in parentheses

Stage Electrician $18 - $25 per week ($409 - $568)

Property Man $18 - $25 per week ($568)

Carpenter $25 - $35 per week ($568 - $795)

Ordinary Stage Hand $12 - $18 per week ($272 -$409)

Show Manager $65 - $125 per week ($1,478 - $2842)

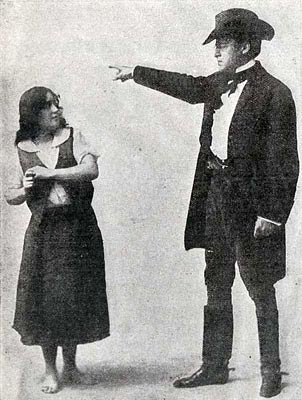

caption: Vaughan Glaser & Fay Compeney in "St Elmo" at the Lyric Theater

And there are five important theaters in Buffalo. If the average is even 40 people to a theater, that would make 200 theater attaches in regular employment besides the extras. The union boasts 150 members in Buffalo. For, indeed, this trade of manipulating the paraphernalia of a theatrical show is a very businesslike one – one that requires quick activity, ready wit and long apprenticeship. But it seems to pay as well as most trades, much better than some.