Wood & Brooks: Ivory Keys and Keyboards

Ontario Street, Tonawanda

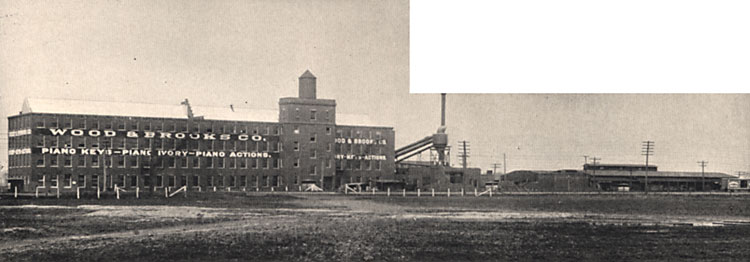

Wood & Brooks factory c. 1907. Image source: private collection

Charles Raymond Wood began his career in 1888 at age 20 working for a Connecticutt company, Pratt, Reed & Company in Ivoryton. It made ivory keys and piano actions. Four years later, he was superintendent of the factory. In 1901, he formed the Wood & Brooks Company with financial assistance from M.S. Brooks, a Connecticut entrepreneur. He moved to Tonawanda to open a plant to manufacture ivory keys and keyboards on Ontario Street. The Niagara Frontier provided him with easy access to lumber, rail lines, and numerous local piano manufacturers in need of keyboards.

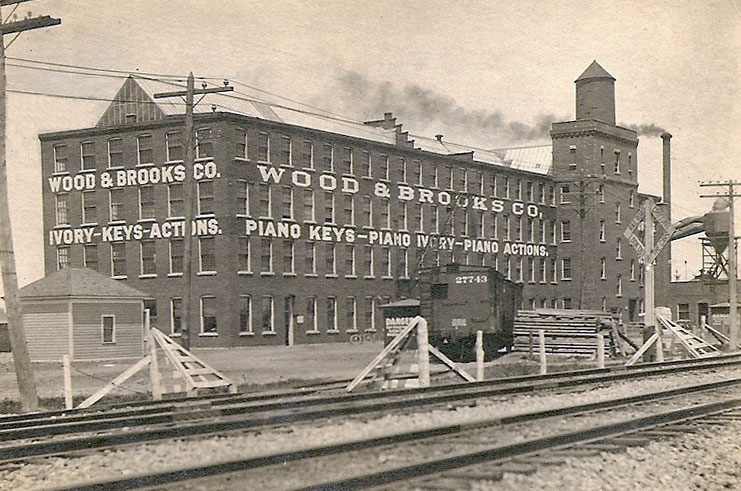

Wood & Brooks factory close view, showing proxmity to railroad tracks. Image source: private collection

Advertisement in Music Trade Review, 1903. Image source: mbsi.org

Charles R. Wood purchased two piano action plants in an aggressive early expansion: Seaverns Action, Cambridge, MA (1905), and Kurtz Action Co., Rockford, IL (1910). He quickly acquired the reputation for excellence in management skills and for paying the highest wages in the area. In 1913, his factory made around 100,000 piano keys annually, from ivory elephant tusks, as well as 100,000 piano actions.

Wood & Brooks, c 1960s. Image source: John Percy

In 1911, the company opened a new building adjacent to its original factory, in buff color above. Wood designed the factory floor for maximum efficiency and fewest "lost motions." He also designed most of the machinery used in the factory, built in his company machine shop. The Tonawanda plant focused on manufacturing piano keys and keyboards, while the other two facilities produced piano actions. The factory on Ontario Street employed around 200 workers.

In a 1939 article, the company claimed that its 150,000 pounds of ivory tusks, representing about 1,000 dead elephants, came largely from elephant graveyards in Africa. The rest came from sport hunters and Africans who killed elephants for their tusks. Each tusk weighed an average of 50 pounds apiece and brought prices ranging from $3 per pound to $10. The average pair of tusks was worth $300. A Buffalonian recalls "seeing railroad flatcars parked on a siding behind the building loaded with elephant tusks arranged like crown roasts of beef, tied in the middle, waiting to be off-loaded." (Felix Klempa)

When the tusks were unloaded, they were stored in a thick-walled, fireproof vault set apart from the factory buildings. Before being processed by skilled craftsmen, the tusks were soaked in water to prevent cracking and chipping.

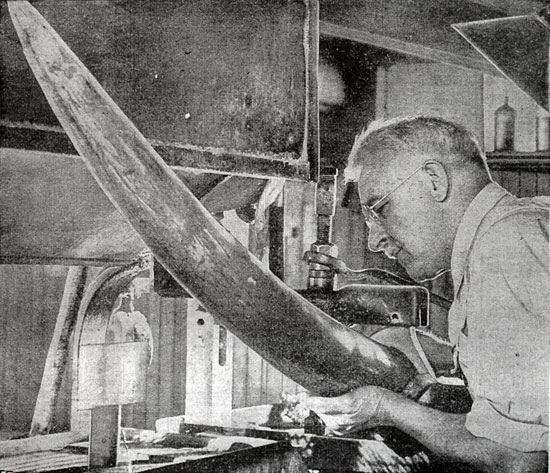

John A. Probst working on an elephant tusk at Wood & Brooks, 1939. Image source: BECPL Scrapbook

About one-third of the tusk was either hollow or wasted in manufacturing; the rest was first cross-cut into four-inch sections. These sections were then marked by an expert who directed the way in which the piece should be cut to obtain the maximum number of piano keys. The final cut, or "slabbing," was done with paper-thin wet saws so that very little was wasted as dust. The finished slabs were 1/20th of an inch thick. In the early days, the yellow ivory slabs were placed in the sun to bleach. By the 1930s, each was treated with a hydrogen peroxide solution and placed in trays in the "greenhouses" in the roof of the factory to whiten. Once that was complete, the slabs were sorted for grain.

Celluloid was used as a subsitute for ivory in piano and organ keys as far back as 1880. Wood and Brooks had reduced its ivory key production to 40% by 1939, the rest produced in celluloid. The ivory keyboards were sold to high-end piano manufacturers such as Steinway. For some afficianodos, the feel of and ivory keyboard remains superior to plastic because ivory absorbs sweat and does not become sticky or slippery from a player's skin oils. (Ebony, which had originally been used to create the black keys, was first replaced by dyed birch and later by plastic.)

Up until World War II, the annual output of the Tonawanda factory was 125,000 keyboards a year. During the war, production was shifted to work as a subcontractor for LCVP (landing craft vehicle, personnel) manufacturing.

Inspecting finished keyboards, 1952. Image source: BECPL Scrapbook

In spite of the emphasis on ivory in the company's logo, most of the work at Wood & Brooks involved wood. From its earliest days in Tonawanda, the factory had been constructing and expanding its lumber sheds. By 1952, the company at its two locations (Tonawanda and Rockford, Illinois) used between 4,000,000 and 5,000,000 board feet of lumber, mostly basswood and maple, to manufacture keys and actions. The maple was used in the Rockford plant to make the actions and the basswood was for the keys themselves. Employment in the early 1950s was 300 people in Tonawanda and 400 in Rockford. Its annual output was 100,000 keyboards in 1952.

John W. Baer, Glenn E. Gordon, Ann Misiak, 1969. Image source: BECPL Scrapbook

In 1952, with 90% of its key production in plastic, Wood & Brooks annually used 25,000 15-foot square sheets of plastic of key coverings. The lumber was kiln-dried, sawed to a specific length and glued to keyboard widths. After planing and marking, the plastic or ivory key veneer was applied and polished, sanded and cleaned. The board was then sawed into individual keys. The company imported 25,000 pound of ivory annually, some of it used in organ keyboards. At that time, the black keys were made at Norton Laboratories in Lockport from Durez plastic. Keyboards and actions were shipped directly to piano manufacturers separately. Steinway, Wurlitzer, Everett were among the name brands that purchased from Wood & Brooks.

In 1954, Wood & Brooks was one of only two keyboard manufacturers nationwide. The company, one of the largest ivory importers in the United States, imported around 10,000 pounds of ivory used for "very expensive pianos,' according to the management.

The company had been operated by three generations of the Wood family. Son Alton Wood was responsible for much of the success in growing the business. In 1954, with grandson Charles H. Wood in charge, the company spent $1,000,000 in modernization of both plants, installing automation for many tasks.

The iconic elephant atop the tower of the 1911 building. The sign was lit by neon. Image source: John Percy

And then in 1958, the company was sold to Sterling Precision Corp, descendent of the Bufflalo-born Sterling Engine Co. Its annual sales were $6,000,000. There were 200 employees in Buffalo and 400 in Rockford. The new owners planned to continue production of the piano parts and also the newer operations at the factory complex: summer leisure furniture and special packaging of finished items.

A year later, the company was sold again, this time to Aurora Corp. of Chicago, at a profit to Sterling. Employment was unchanged at the Tonawanda factory.

2013 view of the former Wood & Brooks factory complex.

Ten years later, the Wood & Brooks company was the largest manufacturer of keyboards in the U.S. but had three floors of its factory vacant. 150 people were employed in Tonawanda and 200 in Rockford. In November, 1969, the owners announced that it would close the Rockford plant, shifting the piano action business to Juarez, Mexico, and consolidate all other operations in Tonawanda. The company also announced a $1,000,000 expenditure for automated equipment.

Six months later, Aurora Corp. shut down the company entirely, blaming competition from Japanese piano manufacturers. Frontier Insulation and Asbestos purchased it.

Faded Wood & Brooks detail visible on the original building.

In 2013, Thermal Foams, Inc. owns the property.

Special thanks to Town of Tonawanda Historian, John Percy, for taking the photos of the Wood & Brooks factory complex prior to the removal of the iconic elephant, and for allowing their use for this story.