From a postcard, c. 1914, 8 Indianola Avenue, Akron NY Image source: private collection

In 1900, Akron NY's formerly robust cement industry was experiencing a sharp decline because Portland cement, a better grade of cement, was becoming the preferred construction material. But that year a new mineral was discovered in Akron that would prove more versatile than the old cement and would provide jobs for decades to come: dihydrous calcium sulfate, gypsum. Word spread far and wide and attracted the attention of an English investor, Simon Peckham, located in London, England. The British had invented "plasterboard" in 1888 by layering plaster within four plies of wood felt paper. Akron's discovery provided an investment opportunity and a Binghamton man, Robert Craig Rose, was hired by Peckham in 1912 to build a factory in Akron to manufacture the plasterboard. Unfortunately, Mr. Rose died suddenly in 1916 and that seems to have been the end of the business. The building, however, would endure.

Akron workers sorting vegetable ivory buttons. Image source: Newstead Historical Society

Records for the button-making industry in Akron are incomplete, but that such a factory would exist is not surprising. By the mid-19th century, Rochester was the second-largest center of the growing ready-to-wear clothing industry (New York City was the leader). The demand for buttons was very high and businesses sprang up all over New York to meet it. Rochester's button manufacturers were leaders in producing pearl buttons, but other factories, like the Akron Button Works (aka Akron Button Company), used "vegetable ivory" to make buttons in a laborious process. The "ivory" material was the seed of the Tagua palm; the nuts were imported cheaply from Central America. The Akron plant would shell the nuts in a large tumbler, sort for size, and cut the nuts on high-speed circular saws into button thicknesses. They then would be steamed to soften them for lathing to shape the buttons, after which holes were drilled and the buttons were polished. Finally, as seen in the photo above, the buttons were inspected and then mounted on cards for sale or display. Loose buttons were sent to the clothing factories. Akron history notes that locals "carded buttons" at home for extra money.

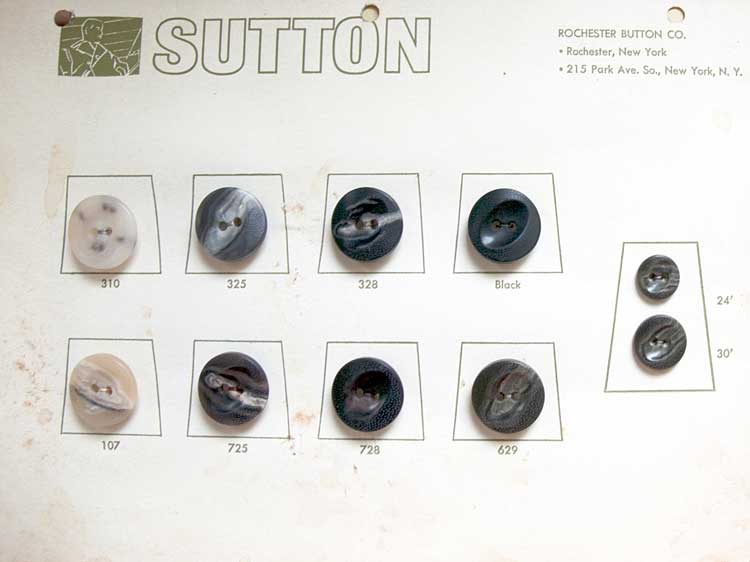

From a display frame of example buttons made from casein in Akron, trimmings at right.

Image source: Newstead Historical Society

In 1917, the Akron Button Factory burned, and it is probable that the factory moved into the former Akron Plasterboard Company building at this time. Around this time, the company was purchased by the Superior Ivory Button Company of Newark, New Jersey, a move that would proved fortuitous for Akron.

After World War I, immense changes to American society put strain on the button industry. Fewer immigrants meant a lack of non-union labor that would work cheaply; clothing styles shifted away from decorative buttons; and zippers were invented. The costly process of making vegetable ivory buttons could not endure and the 243 button factories in New York State, which produced 44.7% of all buttons in the U.S., would have to change or close.

Sample button card. Image source: Newstead Historical Society

Neil Broderson, son of the owner of the Superior Ivory Button Company, was sent to Rochester in 1926 to manage the newly merged company created from the Rochester Button Company, M.B. Shantz Button Company, and Superior. By 1928, he was president of the company and used his creative energies to devise a new method of making buttons, one that would rely on automation and many fewer steps in the process. Over his long career with Rochester Button, he would also design and patent much of its machinery.

Broderson replaced Tagua palm "vegetable ivory" with casein, which was made from skim milk using rennet; 100 pounds of skim milk were needed to make 3 pounds of casein. Because the button industry required a very fine grade of casein powder, it was imported from Germany and Norway. Broderson wanted to reduce this import expenditure and he established a casein plant in Wisconsin near one of that state's largest dairies.

Sample button card. Image source: Newstead Historical Society

The Akron plant of the Rochester Button Factory mixed the casein in large drums, adding liquid and dye. The mixture was then extruded into rods which were then cut by machine into button disks at the rate of 200 disks per minute per machine. The disks were then trimmed by machine for uniformity and sent into a formaldehyde bath for 5 - 20 days. Trimmings were ground up and re-used. After being "fixed" in the formaldehyde, the disks were tumbled in hot air (130 degrees) dryers for 24-48 hours. The button disks were then sent to Rochester for finishing.

Casein was an acceptable button material that saved human labor but it had drawbacks. If a garment with casein buttons was washed in very hot water, the buttons absorbed the water. If ironed, the buttons discolored and became pliable.

Rochester Button Factory, 8 Indianola Avenue, 1941. Image source: Newstead Historical Society

Rochester Button Factory employees, 1941. Image source: Newstead Historical Society

Rochester Button Factory employees, 1941. Image source: Newstead Historical Society

After World War II, only one button manufacturer remained in the U.S.: The Rochester Button Company. In 1948, the company had 750 employees, 500 of them in Rochester. And in 1947, Broderson switched his company to manufacturing buttons from compounds of urea, that is, plastic. And his company's introduction of nacreous polyester, a pearl-like material, finished all use of real pearl buttons on men's shirts.

Despite this innovation, competition emerged from Japanese and Italian button manufacturers. Rochester Button responded in the 1950s by shifting some manufacturing to rural Virginia where labor was inexpensive and non-union. By the early 1960s, the Akron plant was closed. If anyone knows the exact year, please let me know.

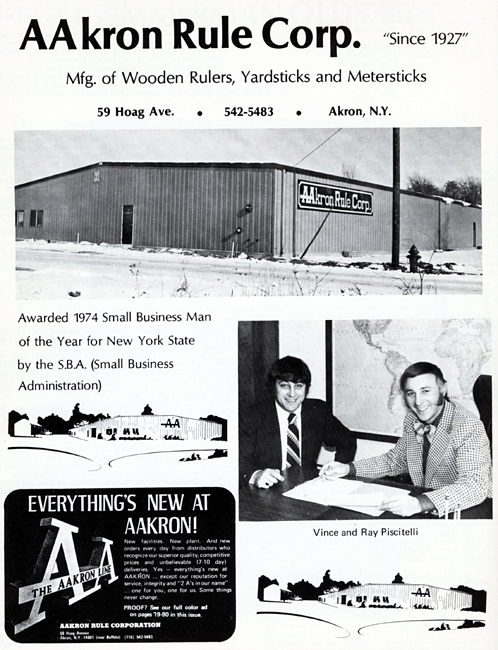

Ad from Akron's 1974 Quasquicentennial book. Image source: Newstead Historical Society

The building was soon to be re-used by Shaw Wood Specialites, which made yardsticks, rulers, and paint paddles. In 1967, brothers Ray and Vince Piscitelli purchased the company, renaming it AAkron Rule. It has expanded in the village and manufactures school and office supplies in addition to promotional products.

8 Indianola Avenue, Akron, in 2012

Thank you, Marybeth Whiting, director of the Knight-Sutton Museum of the Newstead Historical Society and volunteer Tom Valentine for their generous assistance.